ref – https://www.grammar-monster.com/glossary/adjective_clauses.htm

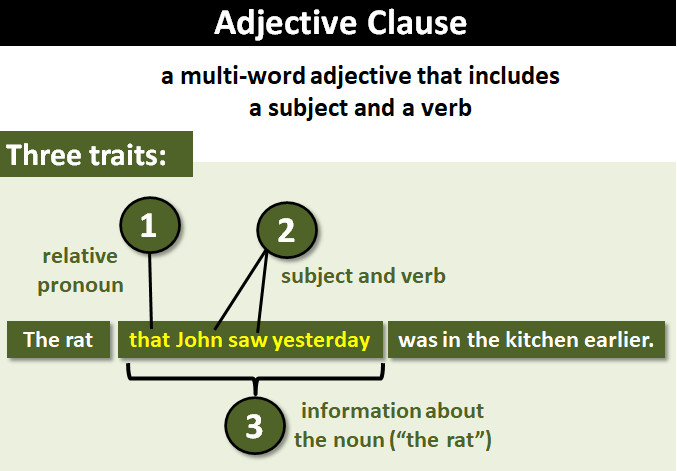

An adjective clause is a multi-word adjective that includes a subject and a verb.

For example:

The painting (subj) we bought last week (adj) is (subj) a fake (obj).

When we think of an adjective, we usually think about a single word used before a noun to modify its meanings (e.g., tall building, smelly cat, argumentative assistant). However, an adjective can also come in the form of an adjective clause. An adjective clause usually comes after the noun it modifies and is made up of several words, which, like all clauses, include a subject and a verb.

When we think of an adjective, we usually think about a single word used before a noun to modify its meanings

- tall building

- smelly cat

- argumentative assistant

However, an adjective can also come in the form of an adjective clause.

An adjective clause usually comes after the noun it modifies and is made up of several words, which, like all clauses, include a subject and a verb.

The Components of an Adjective Clause

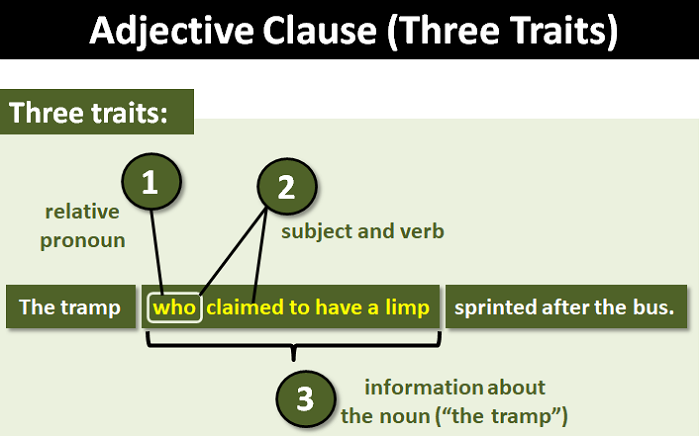

An adjective clause (also called a relative clause) will have the following three traits:

-

Trait 1.

It will start with a relative pronoun (who, whom, whose, that, or which) or a relative adverb (when, where, or why).

This links it to the noun it is modifying.

Note: Quite often, the relative pronoun can be omitted. However, with an adjective clause, it is always possible to put one in.Note – A relative pronoun is a word that introduces a dependent (or relative) clause and connects it to an independent clause. A clause beginning with a relative pronoun is poised to answer questions such as Which one? How many? or What kind? Who, whom, what, which, and that are all relative pronouns.

- Trait 2. It will have a subject and a verb. So that it becomes a clause.

-

Trait 3. It will tell us something about the noun.

(This is why it is a kind of adjective.)

Quite often, the relative pronoun is the subject of the clause. Look at the three traits in this example:

When the adjective clause starts with a relative adverb (when, where or why), the relative adverb cannot be omitted.

I don’t remember a time when words were not dangerous.

(You can often omit a relative pronoun, but you can’t omit a relative adverb. So, you can’t omit when in this example.)

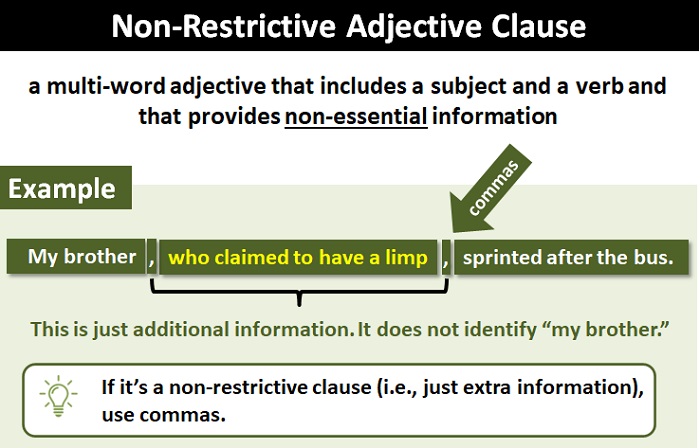

An adjective clause set off from the main clause by commas (one comma if at the beginning or end of a sentence) is said to be nonrestrictive.

Here’s an example:

Old Professor Legree, who dresses like a teenager, is going through his second childhood.

This “who” clause is nonrestrictive because the information it contains doesn’t restrict or limit the noun it modifies, old Professor Legree. Instead, the clause provides added but not essential information, which is signaled by commas. A nonrestrictive adjective clause can be removed without affecting a sentence.

My brother, who claimed to have a limp, sprinted after the bus. √

(This clause is not required to identify My brother. It is added information, so we can add commas.)

My brother (who claimed to have a limp) sprinted after the bus. √

(As it’s just added information, you can put it in brackets.)

My brother sprinted after the bus. √

(You can even delete it.)

Restrictive Adjective Clauses

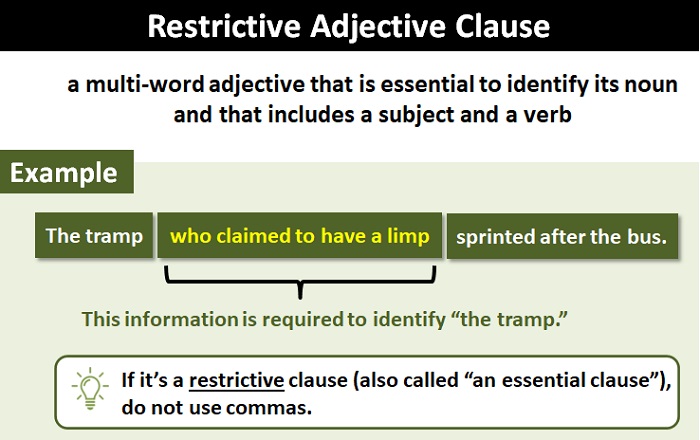

A restrictive adjective clause, on the other hand, is essential to a sentence and should not be set off by commas.

For example:

“An older person who dresses like a teenager is often an object of ridicule. ” √

Here, the adjective clause restricts or limits the meaning of the noun it modifies (an older person).

It should never be:

“An older person, who dresses like a teenager, is often an object of ridicule.” ( X )

as the meaning changes complete. It makes ‘An older person’ into a a singular identified person, which is not the case. We’re talking about ‘an older person’ in general so we should not use commas. Commas are used for optional usage.

(Question 2) What’s the difference between that and which?

Which and that are interchangeable, provided we’re talking about which without a comma.

When which starts a restrictive clause (i.e., a clause not offset with commas), you can replace it with that.

Mark’s dog that ate the chicken is looking guilty.

For many, even Brits, that sounds more natural with a restrictive clause. And, this is something we can use.

The “that substitution” trick also works with who, but be aware that some of your readers might not like that used for people.

The burglar who is suing the homeowner was booed in court.

The burglar that is suing the homeowner was booed in court.

(Substituting who for that is a good way to test whether an adjective clause needs commas or not, but some of your readers might not like ‘that’ being used for a person – even a burglar. So, if your clause starting who sounds okay with that, then revert to who without commas.)