ref –

- http://chineseruleof8.com/code/index.php/2019/01/03/functions-are-first-class-objects-js/

- http://chineseruleof8.com/code/index.php/2019/01/05/currying-js/

- source code

In Redux, we use functional programming paradigm. We use a lot of curry functions like so:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

function add(a) { return function(b) { return a + b; } } let add = add(1); add(5); // 1 + 5 add(1)(5); // 1 + 5 const add2 = a => b => a + b; // you've filled in a as 2 // remember that it returns the function 2 + b let tmp = adds(2); // using the returned function, now you need // to give it another value to get a result tmp(10); // 2 + 10 |

Pure functions

The qualities of a pure function is that there should be:

– no random values

– no current date/time

– no global state (DOM, files, db, etc)

– no mutation of parameters

Benefits are:

– self-documenting

– easily testable

– concurrency

– cacheable

Immutable

Cannot change the objects, but why?

PROS:

Predictability

Faster Change Detection

Concurrency

CONS:

Performance

We use assign to copy contents (properties, values) from one object to another.

|

1 2 3 |

const person = { name: "John" }; const updated = Object.assign({}, person, {age: 30}); console.log(updated); // {name: "John", age: 30} |

|

1 2 3 |

const person = { name: "John" }; const updated = Object.assign({}, person, {name: "bob", age: 30}); console.log(updated); // {name: "bob", age: 30} |

There is an easier way is to do this copying of properties one object to another: spread operator.

We use the spread operator here so that person object’s name property and value “John” gets copied to a new literal object. We then add address property and value.

Finally when we log it, we’ll see the

|

1 2 3 |

const person = { name: "John" }; const updated = {...person, address: "hoho, nowhere, CA, 12345" }; console.log(updated); // {name: "John", address: "hoho, nowhere, CA, 12345" } |

However, it does a shallow copy. Let’s try to copy a object car.

Here when we use the spread operator on person object, it copies the value “John” and property name.

However, it doesn’t copy the object car. Instead, it copies the reference to that object to updated

Therefore, updated only has a reference to the object car.

We can prove this by updating updated.car.carName to “ford”. When we log person.car.carName, it is “ford”

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

const person = { name: "John", car: { carName: 'trumpchi' } }; const updated = {...person, address: "hoho, nowhere, CA, 12345" }; updated.car.carName = "ford"; // person.car.carName is 'ford' |

Hence, spread operator does a shallow copy. It simply re-point address key/value to point to the object that person is referencing. So there’s only 1 object, but two references to it.

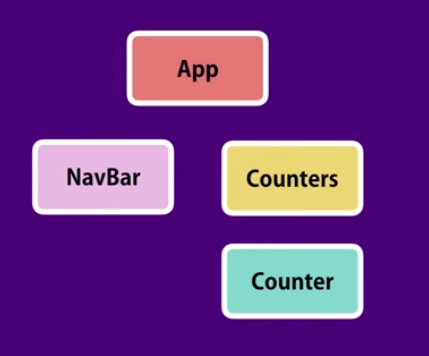

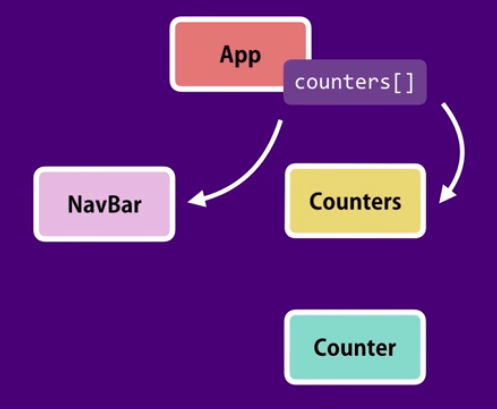

Create Redux app Tutorial

first, lets install redux: npm i redux@4.0

After installation, know that actions is what drives the store to keep your data.

It looks like this:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

{ type: "ADD_QUESTION", // questionAdded payload: { description: "..." } |

So as you can see, its basically an object with properties type and payload.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

{ type: "bugRemoved", payload: { id: 1 } } |

In order to take actions, we must create reducers.

Creating Reducer

Now that we know how actions are put together, we need to write a function in order to decide how we going to properly receive these actions.

In src, add new file reducer.js. A reducer is a function with parameters state and action. The role of the reducer is to return new state, based on incoming actions.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 |

function reducer(state = [], action) { switch(action.type) { case "questionAdded": return [ ...state, { id: ++lastId, description: action.payload.description, resolved: false } ]; case "questionRemoved": return state.filter(question => question.id !== action.payload.id); default: return state; } } |

Hence in our case, we take in the action and look at its type. Depending on the type, we return a certain state.

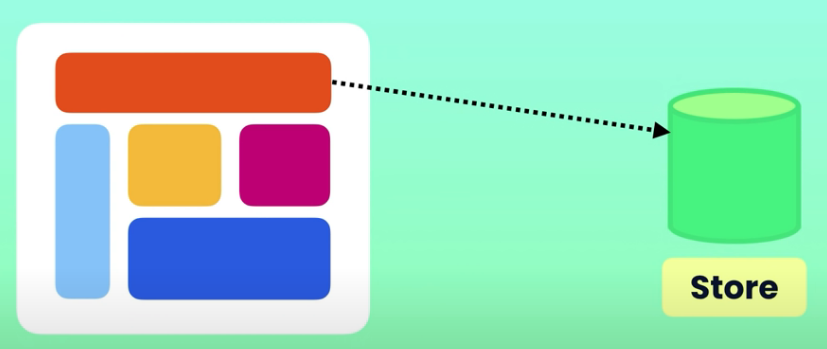

Creating the Store

In src, create new file store.js In our file, we create the store, and then import the reducer because createStore is a first order function that takes in a function (reducer), and returns a store for you to use.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

import { createStore } from 'redux'; import reducer from './reducer'; const store = createStore(reducer); export default store; |

Dispatching Actions

Back in our index, we import our store and analyze its contents.

We use getState function to analyze what is in store in our state.

The initial state is set in our reducer. that is why we see an empty array.

index.js

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 |

import store from './store'; console.log(store); // get the state of the store // should be empty array because that is what we initialized it to be console.log(store.getState()); store.dispatch({ type: 'questionAdded', payload: { description: "Question1" } }); console.log(store.getState()); store.dispatch({ type: 'questionRemoved', payload: { id: 1 } }); console.log(store.getState()); |

We dispatch actions by inserting an object with properties type and payload.

Subscribing to the Store

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 |

import store from './store'; import * as actions from './actionTypes'; const unsubscribe = store.subscribe( () => { console.log('store changed!', store.getState()); }); store.dispatch({ type: actions.QUESTION_REMOVED, payload: { description: "Question1" } }); console.log(store.getState()); unsubscribe(); store.dispatch({ type: actions.QUESTION_REMOVED, payload: { id: 1 } }); console.log(store.getState()); |

Action Creator

dispatching actions takes all this typing and its too cumbersome. Let’s create an action file that does this for us.

Add new file called actions.js

We create another file to keep tract of the MACROS that we’ll be using.

Here, we create es6 functions that returns these action objects. That way our reducer can analyze these action objects to decide what to do next.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 |

import * as actions from './actionTypes'; export const questionAdded = description => ({ type: actions.QUESTION_ADDED, payload: { description } }); export const questionAnswer = (id, answer) => ({ type: actions.QUESTION_ANSWER, payload: { id, answer } }); |

Now, in our reducer, we receives actions like below.

We receive the action object through the action parameter.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 |

export default function reducer(state = [], action) { switch(action.type) { case actions.QUESTION_ADDED: return [ ...state, { id: ++lastId, description: action.payload.description, answer: null } ]; ... .... |

As you can see, its always 2 things:

1) analyze action’s type

2) return state with action’s payload

We use dot operator to copy over primitive types into our new state. However, if there are nested objects, then its only a shallow copy and we need to use libraries such as immer to create immutable state.

reducer.js

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 |

// [] array of questions import * as actions from './actionTypes'; let lastId = 0; // business logic // pure function // called multiplb e times, given same arguments, free of side effects. // give same results export default function reducer(state = [], action) { switch(action.type) { case actions.QUESTION_ADDED: return [ ...state, { id: ++lastId, description: action.payload.description, answer: null } ]; case actions.QUESTION_REMOVED: return state.filter(question => question.id !== action.payload.id); case actions.QUESTION_ANSWER: return state.map(question => { console.log('question', question); if (question.id !== action.payload.id) { return question; } else { return { ...question, answer: action.payload.answer } } }); default: return state; } } |