https://medium.com/javascript-scene/master-the-javascript-interview-what-is-a-closure-b2f0d2152b36

A closure is the local variables for a function – kept alive after the function has returned

In other words,

a closure is formed when an inner functions is made accessible outside of the function in which it was contained, so that it may be executed after the outer function has returned.

At which point it still has access to the local variables, parameters and inner function declarations of its outer function.

Those local variables, parameter and function declarations (initially) have the values that they had when the outer function returned and may be interacted with by the inner function.

1) We get the reference of the returned inner function.

2) Pass in a parameter so its inner function can grab onto it.

3) Execute the reference, which creates scope and grabs.

|

|

function testing123(param) { var name = 'hohoho'; return function () { console.log('Boooom! param is: ' + param); } } var closure = testing123('88'); closure(); |

output:

Boooom! param is: 88

Now we do the same thing, but in a loop.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 |

function testing123(param) { var name = 'hohoho'; return function () { console.log('Boooom! param is: ' + param); } } var closureArr = []; console.log('...ok, so function testing123 has popped'); for (var i = 0; i < 10; i++) { closureArr[i] = testing123(i); } closureArr[0](); closureArr[1](); closureArr[2](); |

output:

Boooom! param is: 0

Boooom! param is: 1

Boooom! param is: 2

…

…

In an async situation, let’s say we have setTimeout that asks for a function to execute when a certain number of seconds have passed.

If we pass a function with a parameter (like what we have above), we’ll be able to have a closure and save state as well. We pass in one variable to the parameter, and the closure references that 1 parameter.

But because we do this in a callback, we must combine the 3 steps together.

So

1) We get the reference of the returned inner function.

2) Pass in a parameter so its inner function can grab onto it.

3) Execute the reference, which creates scope and grabs.

becomes an Immediately Invoked Function Expression:

|

|

function(index) { console.log('setTimeout: ' + index + ' √'); return function() { console.log('After 2 seconds!.....inner func logs: ' + index); } }(88) |

therefore,

|

|

setTimeout(function(index) { console.log('setTimeout: ' + index + ' √'); return function() { console.log('After 2 seconds!.....inner func logs: ' + index); } } (88), 2000); |

First it logs the callback function because we immediately execute it:

‘setTimeout: 88 √’

Then it returns the inner function. Due to the execution of the callback function, the inner function will create scope and reference parameter index from its local.

output:

After 2 seconds!…..inner func logs: 88

Async situation, in a loop:

|

|

for (var i = 0; i < 10; i++) { console.log('for loop: ' + i); // 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 setTimeout(function(index) { console.log('callback: ' + index + ' √'); return function() { console.log('inner func: ' + index); } }(i), 1000); } |

We run an async operation where it executes a function after a second.

The inner function references it parameter, which is passed in via an Immediately Invoked Function Expression.

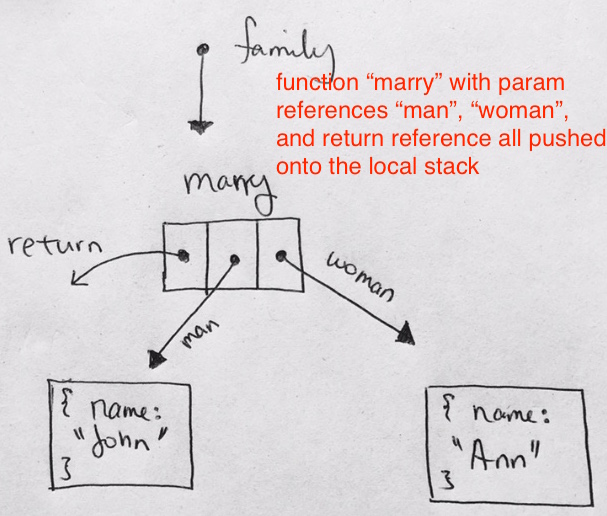

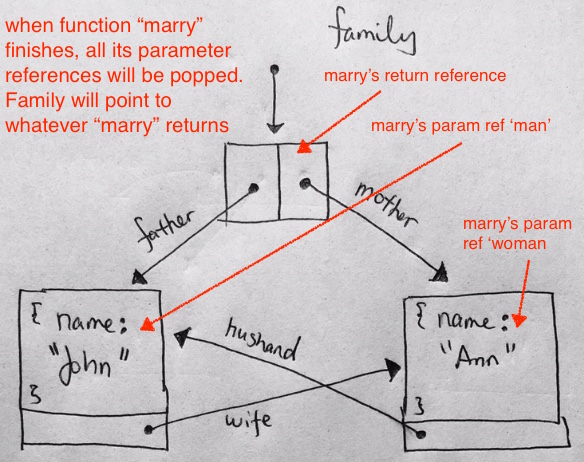

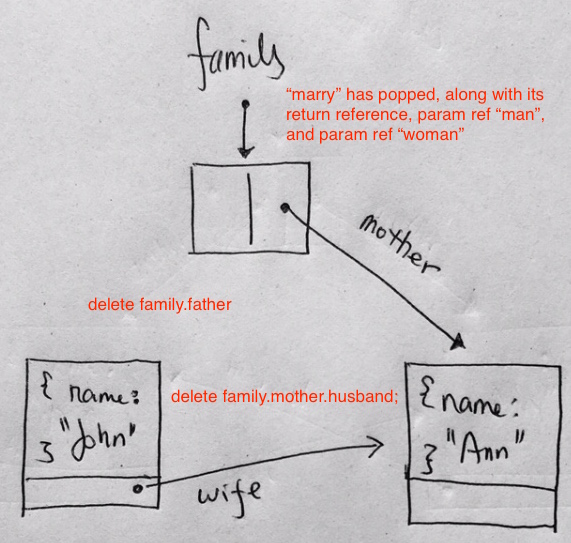

Under the hood, a closure is a stack-frame (which contains accessible variables), which has not been deallocated when the function returns. (as if a ‘stack-frame’ were malloc’ed instead of being on the stack!)

Closures are frequently used in JavaScript for object data privacy, in event handlers and callback functions, and in partial applications, currying, and other functional programming patterns.

What is a Closure?

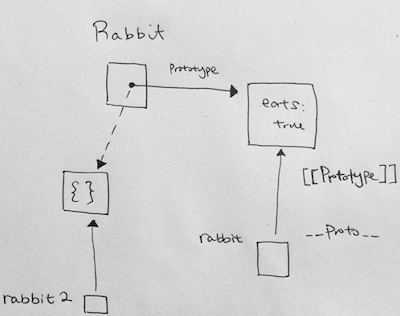

A closure is the combination of a function enclosed with references to its surrounding state (the lexical environment). In other words, a closure gives you access to an outer function’s scope from an inner function. In JavaScript, closures are created every time a function is created, at function creation time.

First, a simple Object with public and private properties

|

|

"use strict"; function Orc(name) { // public property this.name = name || 'green warrior'; var default_weapon = 'hands'; //private }; var blademaster = new Orc('BladeMaster'); console.log("blademaster.name - " + blademaster.name); |

output:

blademaster.name – BladeMaster

Adding public function, and a Closure

To declare a closure, simply define a function inside another function. This is also called an inner function. Inner functions, are private scope by default. You can make it public for instances by assign public properties to it. In other words, you expose the function to be used.

If you assign a property to a function, you make it public and the instance can call it.

However, if its just the function, then it is used as private function for your class to use.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 |

"use strict"; function Orc(newName) { this.name = newName || 'green warrior'; console.log("Constructing Orc: " + this.name) var default_weapon = 'hands'; //private // inner function, private. Only accessible for parent scope function innerFunction() { console.log("This is an inner function"); } // public function bound to an instance of Orc's this this.growls = function(phrase) { console.log(default_weapon); innerFunction(); } } var blademaster = new Orc('BladeMaster'); blademaster.growls("yaar"); |

output:

Constructing Orc: BladeMaster

hands

This is an inner function

Using property variable in closure

After you define the closure, you can simply use the property name as is. i.e property ‘name’ in closure ‘growls’.

Using this.name in the closure vs this.name in the object

Closure has access to

- its own scope

- parent function’s scope

- parent function’s parameters

- DO NOT HAVE ACCESS to parent scope’s this because ‘this’ is inside of a function (either stand-alone or within another method) will always refer to the window/global object.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 |

"use strict"; function Orc(newName) { this.name = newName || 'green warrior'; // public if no closure, private if closure console.log("Constructing Orc: " + this.name) var default_weapon = 'hands'; // 1) has access to own scope's variables // 2) has access parent scope's variables // 3) has access to parent scope's parameter // 4) DOES NOT have access to parent's this scope function inner() { // inner function (closure). var localScopeVar = "local"; console.log(localScopeVar); // 1) console.log(default_weapon); // 2) console.log(newName); // 3) console.log(this.name); // 4) error, 'this' references global object which does not have property name } this.why = function() { // function bound to an Orc instance's this console.log(this.name); inner(); } this.growls = function(phrase) { // function bound to an Orc instance's this console.log(this.name + ": " + phrase); } } var blademaster = new Orc('BladeMaster'); blademaster.name = "Toro"; blademaster.growls("For the burning blade!"); blademaster.why(); |

output:

Constructing Orc: BladeMaster

Toro: For the burning blade!

Toro

local

hands

BladeMaster

ERROR this is undefined

Public properties assigned to Inner Functions can access “this”

Notice that when we assign public properties on Inner Functions, we can access this.

However, a standard inner function (no public properties assigned to it) will not be able to have access to the parent scope’s this.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 |

"use strict"; //http://javascriptissexy.com/understand-javascripts-this-with-clarity-and-master-it/ function User() { this.tournament = "The Masters"; this.data = [{name:"T. Woods", age:37}, {name:"P. Mickelson", age:43}]; // due to public property assigned to this function, we can access this this.clickHandler = function(phrase) { var outerFuncNum = 888; var outerFuncString = "outer limits"; console.log(this.tournament); console.log(this.data); // function is standalone. 'this' references the global object this.data.forEach (function (person) { var ownVarNum = 123; var ownVarString = "hehe"; // It is important to take note that closures cannot access the // outer function’s this variable by using the this keyword because // the this variable is accessible only by the function itself, // not by inner functions. // this inside the anonymous function cannot access the outer function’s this, // so it is bound to the global window object, when strict mode is not being used. console.log("1) own vars"); console.log(ownVarNum); console.log(ownVarString); console.log("2) outer function's vars"); console.log(outerFuncNum); console.log(outerFuncString); console.log("3) outer function's parameter"); console.log(phrase); console.log ("4) Inside closure: " + this); // global }) } } var user = new User(); user.clickHandler("merry xmas!"); |

output:

The Masters

who’s playing in it!?

[ { name: ‘T. Woods’, age: 37 },

{ name: ‘P. Mickelson’, age: 43 } ]

1) own vars

123

hehe

2) outer function’s vars

888

outer limits

3) outer function’s parameter

merry xmas!

4) Inside closure: undefined

1) own vars

123

hehe

2) outer function’s vars

888

outer limits

3) outer function’s parameter

merry xmas!

4) Inside closure: [global object]

If we do want private inner function to access parent scope

see http://chineseruleof8.com/code/index.php/2018/02/07/arrow-functions-js/ for detailed explanation

of using 3 ways to how to use ‘this’ in inner functions:

Using parent scope variable

Using bind or call

Using arrow

More Example

First, we create the Person object. In the constructor declaration, we have a private property called pvtArray.

Any functions within our class Person can access it as a outer scope, global variable.

We have a public property called nickname. This property is accessed with this within our class Person.

|

|

function Person() { // constructor declarations var pvtArray = ["ricky", "dean", "charles"]; this.nickname = "Qiji"; ... ... } |

However, there is a caveat.

Let’s say we declare a public function called displayInfo. It is considered a 1st layer function and can see the ‘this’ object.

Any functions within function displayInfo are considered (2nd and later) functions. These functions cannot see the ‘this’ object and any reference to this will result in undefined.

Thus, in Person, if you are to see the commented out setTimeout function, this.nickname will be undefined because ‘this’ references Timeout’s this. In Timeout, there is no property nickname.

|

|

function Person() { .... .... this.displayInfo = function (callback) { console.log(this.nickname); // valid setTimeout(function() { // 3rd level and up function console.log("ha dooo ken!"); console.log(this.nickname); // undefined because this references TimeOut object. Property nickname DNE. console.log(pvtArray); }, 2000); } ... } |

As mentioned earlier, we can use any of the 3 ways to bind ‘this’ to the correct context: fat arrow, local stack ‘self’, or bind.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 |

function Person() { // constructor declarations var pvtArray = ["ricky", "dean", "charles"]; this.nickname = "Qiji"; this.displayInfo = function (callback) { console.log(this.nickname); // arrow func binds to this obj setTimeout(() => { console.log("ha dooo ken!"); console.log(this.nickname); // property acces console.log(pvtArray); // outer scope access callback(); }, 2000); } } |

Now we are going to write a Boss class. This Boss class has a public function called peekOnRandomEmployee.

We declare a new Person in that function. Then directly call displayInfo on it.

displayInfo needs a anonymous function as a parameter for its callback. We declare a anonymous function and pass it in.

The point here is that our anonymous function is a 2nd and later level function. Thus, its ‘this’ reference is on Timeout.

If we are to use the fat arrow function, the ‘this’ will then be assigned to its parent context. Its parent context is the instance. Hence, our ‘this’ inside the callback will be assigned to the instance.

Boss example

Notice how it references outer function variables a and p. By definition, a function’s scope extends to all variables

and parameters declared by its surrounding parents. And of course any global variables as dictated by scope rules.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 |

function Person() { // constructor declarations var pvtArray = ["ricky", "dean", "charles"]; this.nickname = "Qiji"; this.displayInfo = function (callback) { console.log(this.nickname); // arrow func binds to this obj setTimeout(() => { console.log("ha dooo ken!"); console.log(this.nickname); console.log(pvtArray); callback(); }, 2000); } } var gVar = "global here"; function Boss() { this.bossName = "Big boss"; let yoyo = "yoyo"; this.peekOnRandomEmployee = function() { let a = "halo"; var p = new Person(); p.displayInfo(() => { console.log("missions complete"); console.log("by - " + this.bossName); console.log(a); // closure has reference to outer function variables console.log(yoyo); // closure has reference to outer outer function variable console.log(gVar); // closure has reference to global function variable }); } } var b = new Boss(); b.peekOnRandomEmployee(); |