https://hackernoon.com/prototypes-in-javascript-5bba2990e04b

Object.prototype is one of the rare objects that has no prototype: it does not inherit

any properties.

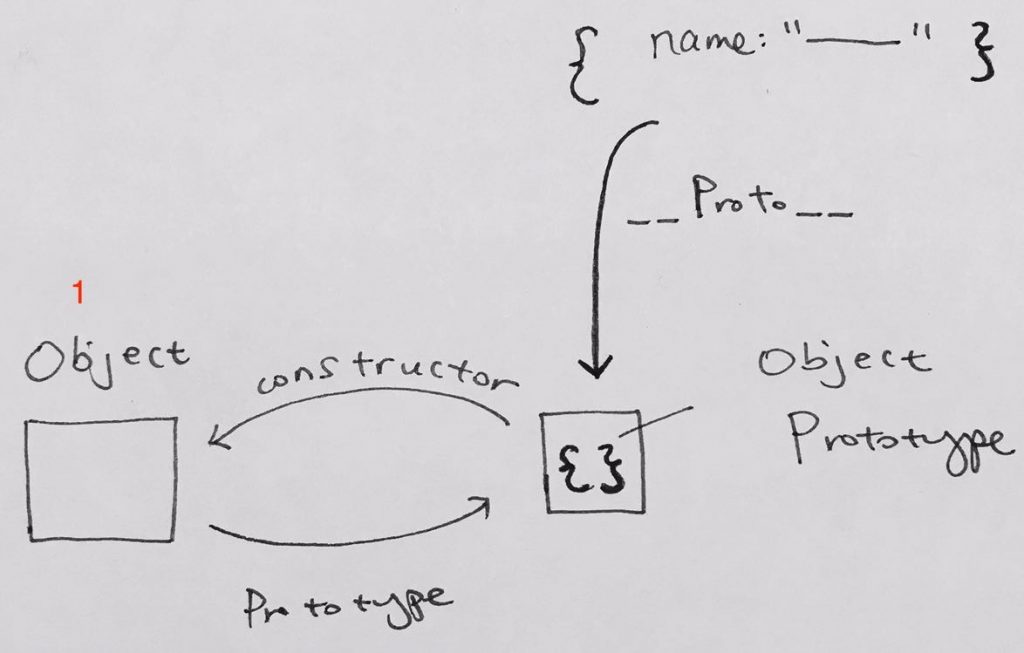

Step 1:

Every object in Javascript is derived from base Object. Base Object has many built-in properties, with its prototype pointing to an empty “Object prototype”. Hence, in memory we see “function Object” which has a prototype property referencing Object Prototype. Then it has a constructor reference coming back to Object.

Thus, when we create our literal object (with a name property in there), it derives from Object. Thus, it has its reference __proto__ pointing to Object Prototype.

That is why when you see an instance of Object (object literal) and Object, their prototype and constructor are the same.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

var objLiteral = { name: "not entered" } console.log("--- Object ---"); console.log(Object.prototype); // {} console.log(Object.prototype.constructor); // [Function: Object] console.log("----------------------"); console.log("--- object literal ---"); console.log(objLiteral.__proto__); // {} console.log(objLiteral.__proto__.constructor); // [Function: Object] console.log("----------------------"); |

Object.prototype –> {}

Object.prototype.constructor); –> [Function: Object]

objLiteral.__proto__ –> {}

objLiteral.__proto__.constructor –> [Function: Object]

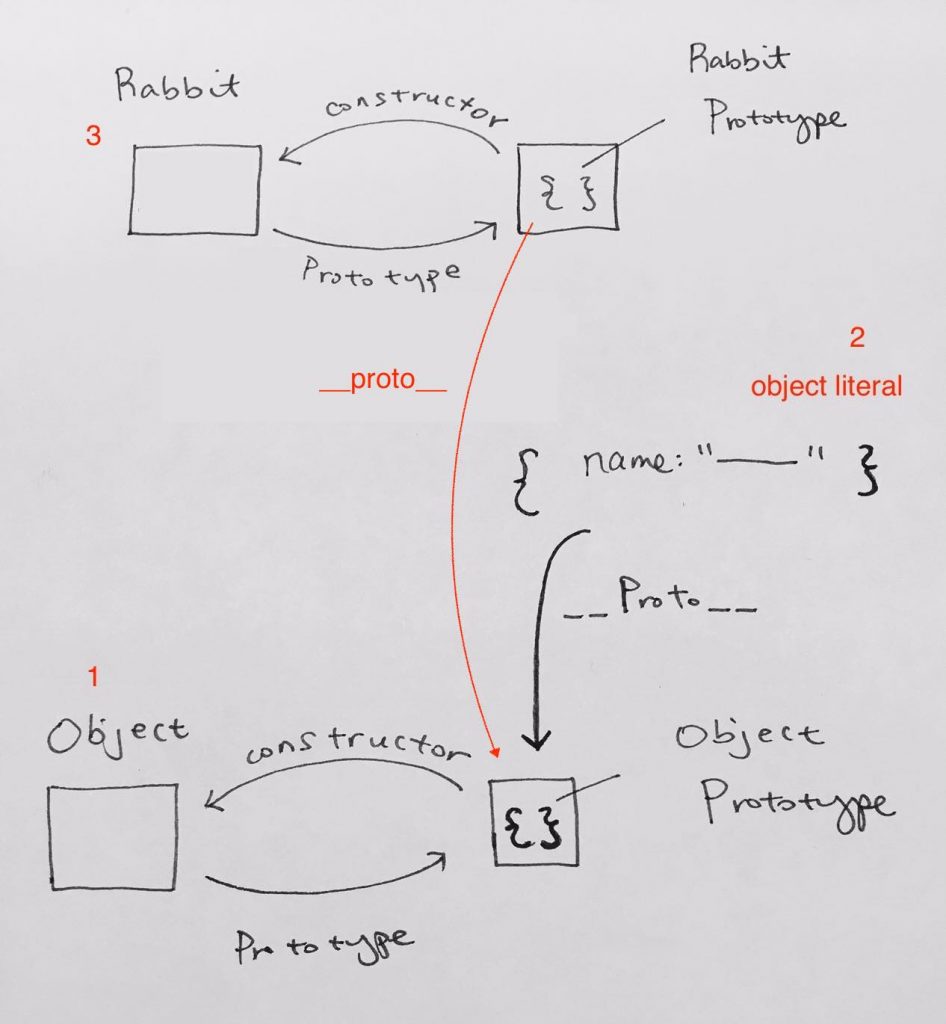

Step 2 – Creating the Rabbit object

Now we create a Rabbit object. Therefore, by definition, Rabbit has a prototype reference pointing to an empty Rabbit Prototype. The Rabbit Prototype has a constructor pointing back to the Rabbit definition. But remember, every object in Javascript derives from Object. Hence Rabbit’s Prototype object is actually an object literal that has a __proto__ pointing to Object Prototype.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

function Rabbit() { console.log("Rabbit Constructor"); } console.log(Rabbit.prototype); // Rabbit {} console.log(Rabbit.prototype.constructor); // [Function: Rabbit] console.log(Rabbit.prototype.__proto__); // {} console.log(Rabbit.prototype.__proto__.constructor); // [Function: Object] |

So as you see, Rabbit’s prototype and prototype.constructor is very straight forward. But it will be surprising to the reader that Rabbit.prototype has a __proto__ property. That is because Rabbit.prototype itself is an empty object literal. And like any object in JS, it derives from Object. Thus, that is why Rabbit.prototype.__proto__.constructor is [Function: Object].

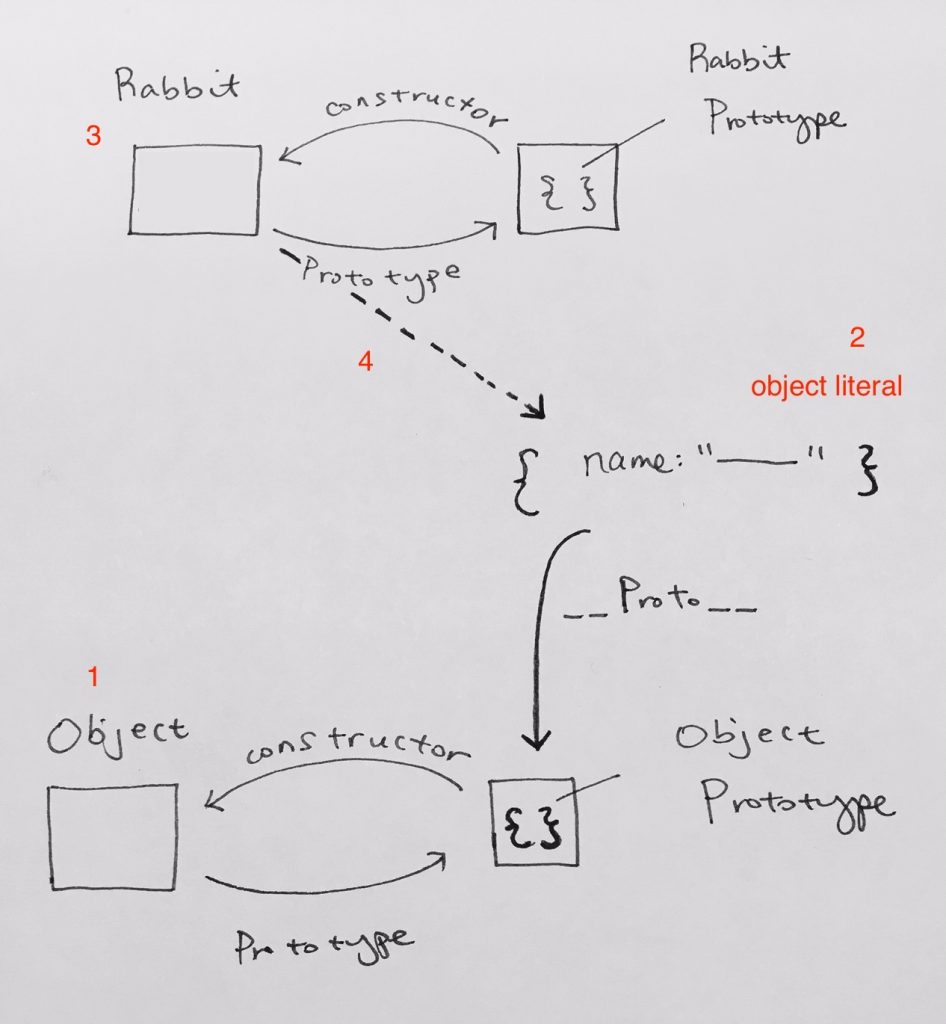

Step 3 – Connecting the Rabbit object

So now, let’s connect the Rabbit’s prototype to some other object literal instead of the empty default one given to us. Say an object literal with property name, initialized to “not entered”. In memory it will looks like this:

As stated earlier, any object in JS has a __proto__ pointing to Object.prototype. Thus, the object literal we created also has this. When we connect our Rabbit.prototype to it, the Rabbit’s prototype takes on the object literal.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

var objLiteral = { name: "not entered" } console.log("Rabbit.prototype = objLiteral") Rabbit.prototype = objLiteral; console.log("--- Rabbit ---"); console.log(Rabbit.prototype); // { name: 'not entered' } console.log(Rabbit.prototype.__proto__); // {} console.log(Rabbit.prototype.constructor); // [Function: Object] console.log("----------------------"); |

Rabbit.prototype –> { name: ‘not entered’ }

Rabbit.prototype.__proto__ –> {}

Rabbit.prototype.constructor –> [Function: Object]

An interesting thing to note here is that when evaluating Rabbit.prototype.constructor, since

Rabbit.prototype is { name: ‘not entered’ }, and we call constructor on it, it does not exist.

So what it does is that it tries to find property “constructor” on object’s __proto__, which is

Object.prototype. It exists (Object.prototye.constructor), and it points to [Function: Object].

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

Rabbit.prototype.copy = function() { // return new Person(this.name); // just as bad return new Rabbit(); }; console.log(Rabbit.prototype); // { name: 'not entered', copy: [Function] } console.log(Rabbit.prototype.constructor); // [Function: Object] var a = new Rabbit(); console.log(a.__proto__); // { name: 'not entered', copy: [Function] } console.log(a.__proto__.constructor); // [Function: Object] |

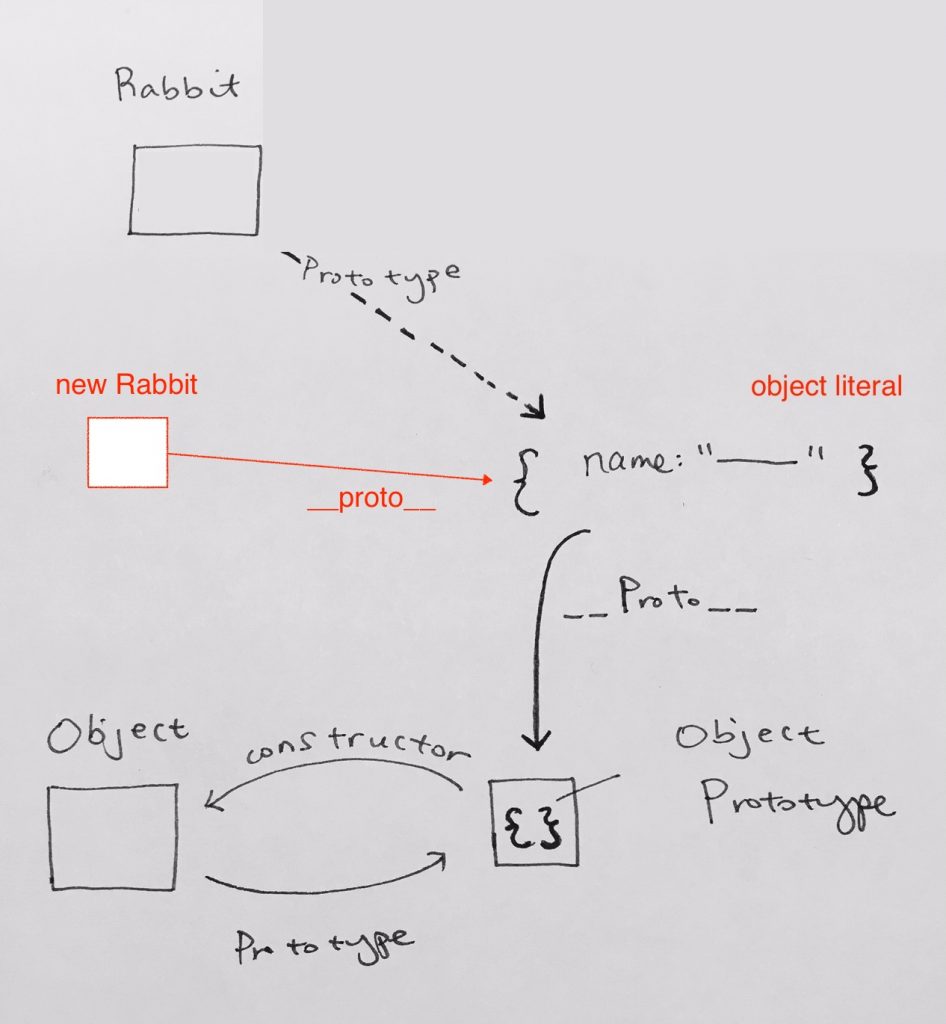

Instantiations of Rabbit

Prototype Chain

From all the information presented above, all prototype objects (except Object.prototype) are normal objects that do have a prototype. All of the built-in constructors (and most user-defined constructors) have a prototype that inherits from Object.prototype.

For example, Date.prototype inherits properties from Object.prototype, so a Date object created by new Date() inherits properties from both Date.prototype and Object.prototype.

This linked series of prototype objects is known as a prototype chain.

The problem with Prototoypes

As prototype object is shared among all the objects created using the constructor function, it’s properties and methods are also shared among all the objects. If an object A modifies property of the prototype having primitive value, other objects will not be effected by this as A will create a property on its objects.

If you were to create many rabbit instances, and then change the property name in its __proto__, all other rabbits will be affected.

Solution – Combine Constructor/Prototype

We know 2 things:

- Every object calls the constructor and thus, gets its own instance of the function definition, along with its own properties.

- Modifying a Prototype property using one instance reflects the other instances also.

What we can do is to define all the object specific properties inside the constructor and all shared properties and methods inside the prototype as shown below:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 |

//Define the object specific properties inside the constructor function Human(name, age){ this.name = name, this.age = age, this.friends = ["Jadeja", "Vijay"] } //Define the shared properties and methods using the prototype Human.prototype.sayName = function(){ console.log(this.name); } //Create two objects using the Human constructor function var person1 = new Human("Virat", "Kohli"); var person2 = new Human("Sachin", "Tendulkar"); //Lets check if person1 and person2 have points to the same instance of the sayName function console.log(person1.sayName === person2.sayName) // true //Let's modify friends property and check person1.friends.push("Amit"); console.log(person1.friends); // Output: "Jadeja, Vijay, Amit" console.log(person2.frinds); //Output: "Jadeja, Vijay" |

Full Source to Rabbit example

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 |

function Rabbit() { console.log("Rabbit Constructor"); } console.log(Rabbit.prototype); console.log(Rabbit.prototype.__proto__); console.log(Rabbit.prototype.__proto__.constructor); console.log(Rabbit.prototype.constructor); var objLiteral = { name: "not entered" } console.log("--- object literal ---"); console.log(objLiteral.__proto__); console.log(objLiteral.__proto__.constructor); console.log("----------------------"); console.log(Object.prototype); console.log(Object.prototype.constructor); console.log("----------------------"); console.log("Rabbit.prototype = objLiteral") Rabbit.prototype = objLiteral; console.log("--- Rabbit ---"); console.log(Rabbit.prototype); // { name: 'not entered' } console.log(Rabbit.prototype.__proto__); // {} console.log(Rabbit.prototype.constructor); // [Function: Object] console.log("----------------------"); Rabbit.prototype.copy = function() { // return new Person(this.name); // just as bad return new Rabbit(); }; console.log(Rabbit.prototype); console.log(Rabbit.prototype.constructor); var a = new Rabbit(); console.log(a.__proto__); console.log(a.__proto__.constructor); |

OUTPUT

Rabbit {}

{}

[Function: Object]

[Function: Rabbit]

— object literal —

{}

[Function: Object]

———————-

{}

[Function: Object]

———————-

Rabbit.prototype = objLiteral

— Rabbit —

{ name: ‘not entered’ }

{}

[Function: Object]

———————-

{ name: ‘not entered’, copy: [Function] }

[Function: Object]

Rabbit Constructor

{ name: ‘not entered’, copy: [Function] }

[Function: Object]