|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 |

import React, { useState, useEffect } from 'react'; import './App.css'; function App() { const [counter, setCounter] = useState(0); console.log('App', 'start point'); useEffect(() => { console.log('useEffect', 'start point'); setTimeout(() => { console.log('setTimeout', 'setCounter to 1'); // first time, it sets the 0 to 1. So we call render. Math.random() runs // 2nd time, tries to set 1 to 1, no render gets called. No Math.random(). // https://en.reactjs.org/docs/hooks-reference.html#bailing-out-of-a-state-update // If you update a State Hook to the same value as the current state, // React will bail out without rendering the children or firing effects. setCounter(1); }, 5000); }); // initially, counter is 0, then Math.random() is called return ( <div className="ticker" > <b>{Math.random()}</b> <div> <div className="ticker-name">{counter}</div> </div> </div> ); } export default App; |

All posts by admin

Hooks (React)

ref – https://reactjs.org/docs/hooks-state.html

Initially, there was function components, and class components:

– Functional components does not have state. Nor does it have lifecycle functions.

– Class components have state, and has lifecycle functions.

However, with the introduction of Hooks, in functional components, we now can have state and lifecycle functionality.

Hooks – JS functions that lets you ‘hook into’ React State and LifeCycle features within your functional component.

– DOES NOT work inside class components.

– ONLY call top level. Don’t call hooks inside loops, conditions, standard functions, or nested functions.

– ONLY call from Functional Components.

Many hooks exists. You can even write your own. Let’s take a look at an very basic hook, useState

When would I use a Hook?

If you write a function component and realize you need to add some state to it, previously you had to convert it to a class. Now you can use a Hook inside the existing function component. We’re going to do that right now!

Hook useState returns a pair of state. A state value, and a setState value.

|

1 2 3 |

function example() { const [ count, setCount ] = useState(0); } |

Whatever name you get first is to get the state property. The second parameter you simply add a set to it to say you want to set this state property.

The 0 is the default value we want to give for our state property.

|

1 2 3 |

const [age, setAge] = useState(42); const [fruit, setFruit] = useState('banana'); const [todos, setTodos] = useState([{...}, {...}, {...}]); |

We use it like so. We declare count value, set its default to 0, and then declare its set functionality setCount.

We then can set it in our JSX.

In order to set new count, we simply use setCount.

In order to use it, we simply use the variable count.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 |

import React, { useState } from 'react'; function Example() { // Declare a new state variable, which we'll call "count" const [count, setCount] = useState(0); return ( <div> <p>You clicked {count} times</p> <button onClick={() => setCount(count + 1)}> Click me </button> </div> ); } |

UseEffect

The Effect Hook lets you perform side effects in function components

– Data fetching

– subscribing

– manually changing the DOM

are all examples of side effects. We call these operations “side effects” (or “effects” for short) because they can affect other components and can’t be done during rendering.

The Effect Hook, useEffect, adds the ability to perform side effects from a function component. It serves the same purpose as componentDidMount, componentDidUpdate, and componentWillUnmount in React classes, but unified into a single API. (We’ll show examples comparing useEffect to these methods in Using the Effect Hook.)

When you call useEffect, you’re telling React to run your “effect” function after flushing changes to the DOM.

Effects are declared inside the component so they have access to its props and state. By default, React runs the effects after every render — including the first render.

What does useEffect do? By using this Hook, you tell React that your component needs to do something after render. React will remember the function you passed (we’ll refer to it as our “effect”), and call it later after performing the DOM updates. In this effect, we set the document title, but we could also perform data fetching or call some other imperative API.

Why is useEffect called inside a component? Placing useEffect inside the component lets us access the count state variable (or any props) right from the effect. We don’t need a special API to read it — it’s already in the function scope. Hooks embrace JavaScript closures and avoid introducing React-specific APIs where JavaScript already provides a solution.

Does useEffect run after every render? Yes!

By default, it runs both after the first render and after every update. Instead of thinking in terms of “mounting” and “updating”, you might find it easier to think that effects happen “after render”. React guarantees the DOM has been updated by the time it runs the effects.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 |

import React, { useState, useEffect } from 'react'; function Example() { const [count, setCount] = useState(0); // Similar to componentDidMount and componentDidUpdate: useEffect(() => { // Update the document title using the browser API document.title = `You clicked ${count} times`; }); return ( <div> <p>You clicked {count} times</p> <button onClick={() => setCount(count + 1)}> Click me </button> </div> ); } |

Example

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

function Example() { const [count, setCount] = useState(0); useEffect(() => { document.title = `You clicked ${count} times`; }); } |

We declare the count state variable, and then we tell React we need to use an effect. We pass a function to the useEffect Hook. This function we pass is our effect. Inside our effect, we set the document title using the document.title browser API. We can read the latest count inside the effect because it’s in the scope of our function. When React renders our component, it will remember the effect we used, and then run our effect after updating the DOM. This happens for every render, including the first one.

Experienced JavaScript developers might notice that the function passed to useEffect is going to be different on every render. This is intentional. In fact, this is what lets us read the count value from inside the effect without worrying about it getting stale. Every time we re-render, we schedule a different effect, replacing the previous one. In a way, this makes the effects behave more like a part of the render result — each effect “belongs” to a particular render.

When exactly does React clean up an effect? React performs the cleanup when the component unmounts. However, as we learned earlier, effects run for every render and not just once.

This is why React also cleans up effects from the previous render before running the effects next time.

We’ll discuss why this helps avoid bugs and how to opt out of this behavior in case it creates performance issues later below.

ref – https://reactjs.org/docs/hooks-effect.html#tip-optimizing-performance-by-skipping-effects

Explanation: Why Effects Run on Each Update

Note – Update in this case means that the useState’s previous and current state are DIFFERENT

If the previous and current state are the same, then React will bail out, and none of the children of the component will be rendered.

If you’re used to classes, you might be wondering why the effect cleanup phase happens after every re-render, and not just once during unmounting. Let’s look at a practical example to see why this design helps us create components with fewer bugs.

Earlier on this page, we introduced an example FriendStatus component that displays whether a friend is online or not. Our class reads friend.id from this.props, subscribes to the friend status after the component mounts, and unsubscribes during unmounting:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

componentDidMount() { ChatAPI.subscribeToFriendStatus( this.props.friend.id, this.handleStatusChange ); } componentWillUnmount() { ChatAPI.unsubscribeFromFriendStatus( this.props.friend.id, this.handleStatusChange ); } |

But what happens if the friend prop changes while the component is on the screen? Our component would continue displaying the online status of a different friend. This is a bug. We would also cause a memory leak or crash when unmounting since the unsubscribe call would use the wrong friend ID.

In a class component, we would need to add componentDidUpdate to handle this case:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 |

componentDidMount() { ChatAPI.subscribeToFriendStatus( this.props.friend.id, this.handleStatusChange ); } componentDidUpdate(prevProps) { // Unsubscribe from the previous friend.id ChatAPI.unsubscribeFromFriendStatus( prevProps.friend.id, this.handleStatusChange ); // Subscribe to the next friend.id ChatAPI.subscribeToFriendStatus( this.props.friend.id, this.handleStatusChange ); } componentWillUnmount() { ChatAPI.unsubscribeFromFriendStatus( this.props.friend.id, this.handleStatusChange ); } |

Forgetting to handle componentDidUpdate properly is a common source of bugs in React applications.

Now consider the version of this component that uses Hooks:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

function FriendStatus(props) { useEffect(() => { // this effect ChatAPI.subscribeToFriendStatus(props.friend.id, handleStatusChange); // clean up this effect return () => { ChatAPI.unsubscribeFromFriendStatus(props.friend.id, handleStatusChange); }; }); |

This behavior ensures consistency by default and prevents bugs that are common in class components due to missing update logic.

Mount with { friend: { id: 100 } } props

DOM gets updated. Causes previous clean up effect to be called.

There is none, so our to be called after the render.

|

1 |

ChatAPI.subscribeToFriendStatus(100, handleStatusChange); // Run first effect |

Update with { friend: { id: 200 } } props

DOM gets updated. Causes returned effect clean up effect to be called.

|

1 |

ChatAPI.unsubscribeFromFriendStatus(100, handleStatusChange); // Clean up previous effect |

Render complete, call current effect

|

1 |

ChatAPI.subscribeToFriendStatus(200, handleStatusChange); // Run next effect |

Update with { friend: { id: 300 } } props

DOM gets updated. Causes returned cleanup effect function to be called.

|

1 |

ChatAPI.unsubscribeFromFriendStatus(200, handleStatusChange); // Clean up previous effect |

Render complete. calls current effect

|

1 |

ChatAPI.subscribeToFriendStatus(300, handleStatusChange); // Run next effect |

As times goes by…or when app quits, it will call update one last time.

The previous clean up effect function executes.

Causes returned cleanup effect function to be called.

|

1 2 |

// Unmount ChatAPI.unsubscribeFromFriendStatus(300, handleStatusChange); // Clean up last effect |

Optimizing Performance by Skipping Effects

As shown, cleaning up and/or applying the effect after every render might create a performance problem in some cases.

In class components, we can solve this by writing an extra comparison with prevProps or prevState inside componentDidUpdate:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

componentDidUpdate(prevProps, prevState) { if (prevState.count !== this.state.count) { document.title = `You clicked ${this.state.count} times`; } } |

This requirement is common enough that it is built into the useEffect Hook API. You can tell React to skip applying an effect if certain values haven’t changed between re-renders. To do so, pass an array as an optional second argument to useEffect:

|

1 2 3 |

useEffect(() => { document.title = `You clicked ${count} times`; }, [count]); // Only re-run the effect if count changes |

In the example above, we pass [count] as the second argument. What does this mean? If the count is 5, and then our component re-renders with count still equal to 5, React will compare [5] from the previous render and [5] from the next render. Because all items in the array are the same (5 === 5), React would skip the effect. That’s our optimization.

When we render with count updated to 6, React will compare the items in the [5] array from the previous render to items in the [6] array from the next render. This time, React will re-apply the effect because 5 !== 6. If there are multiple items in the array, React will re-run the effect even if just one of them is different.

This also works for effects that have a cleanup phase:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

useEffect(() => { function handleStatusChange(status) { setIsOnline(status.isOnline); } ChatAPI.subscribeToFriendStatus(props.friend.id, handleStatusChange); return () => { ChatAPI.unsubscribeFromFriendStatus(props.friend.id, handleStatusChange); }; }, [props.friend.id]); // Only re-subscribe if props.friend.id changes |

Creating basic custom Hook

We create a get and set for our property.

get property is pretty standard so we just leave it.

We can over the set property by declaring another function name and using the default set property function from useState.

After we’re done, we simply create a literal object, insert those properties, and return it

userOrderCount.js

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 |

import { useState } from 'react'; function useOrderCountHook() { // already declared function to get order count const [orderCount, setOrderCount] = useState({ count: 0 }); // implement the setOrderCount const changeOrderCount = () => { setOrderCount({ count: orderCount.count + 1 }) } // put both properties into object to be returned and used return { orderCount, changeOrderCount }; } export default useOrderCountHook; |

We import it into main. Then simply use those properties as see fit. Put the get into the view.

Put the set as callback of the interactive controls.

App.js

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 |

function App() { const orderHook = userOrderCountHook(); return ( <div className="App"> <header className="App-header"> <h1>count: {orderHook.orderCount.count}</h1> <img src={logo} className="App-logo" alt="logo" /> <button onClick={orderHook.changeOrderCount}> increment </button> </header> </div> ); } export default App; |

Memoization Components

ref –

- https://medium.com/@rossbulat/how-to-memoize-in-react-3d20cbcd2b6e

- https://dmitripavlutin.com/use-react-memo-wisely/ https://medium.com/@trekinbami/using-react-memo-and-memoization-1970eb1ed128

- https://medium.com/@reallygordon/implementing-memoization-in-javascript-5d140bb04166

- https://blog.bitsrc.io/improve-react-app-performance-through-memoization-cd651f561f66

- https://reactgo.com/react-usememo-example/

Memoization is the process of caching a result of inputs linearly related to its output, so when the input is requested the output is returned from the cache instantaneously.

Memoization is an optimization technique used to primarily speed up programs by storing the results of expensive function calls and returning the cached results when the same inputs occur again.

Say we have a simple function that calculates the Fibonacci number like so:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

// original function function recursiveFib(n) { if (n <= 1) {return n} return recursiveFib(n-1) + recursiveFib(n-2) } |

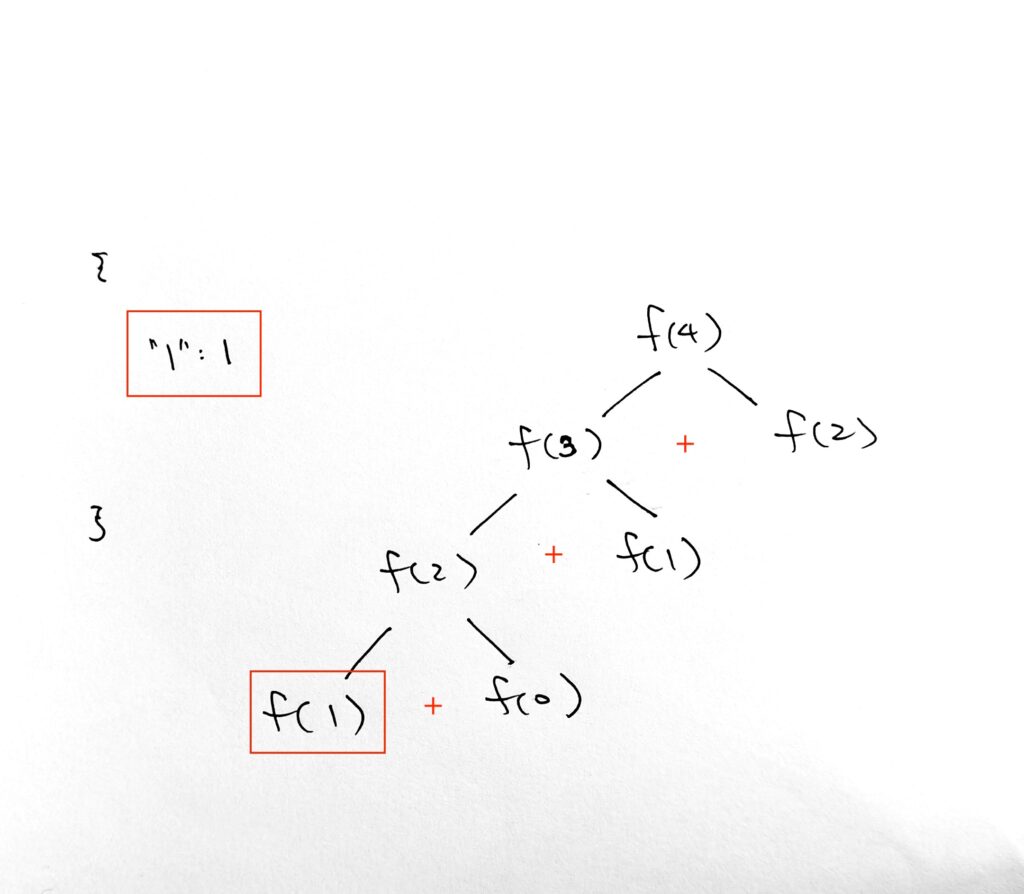

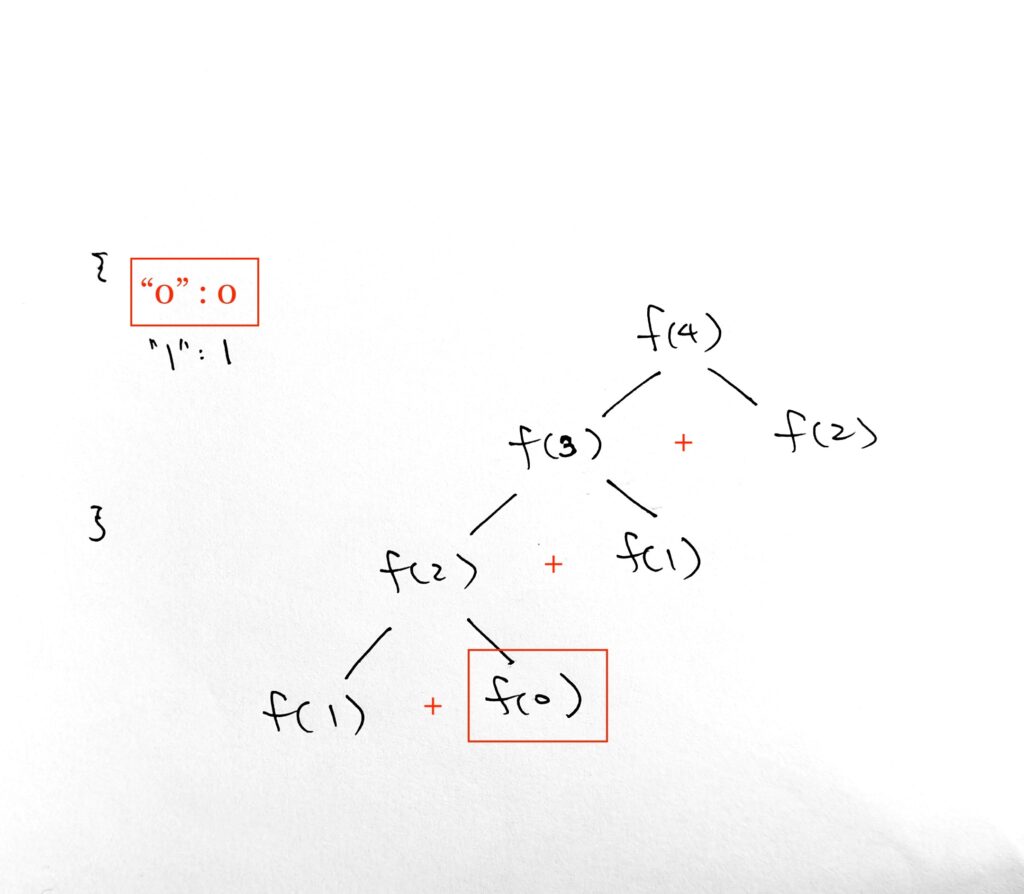

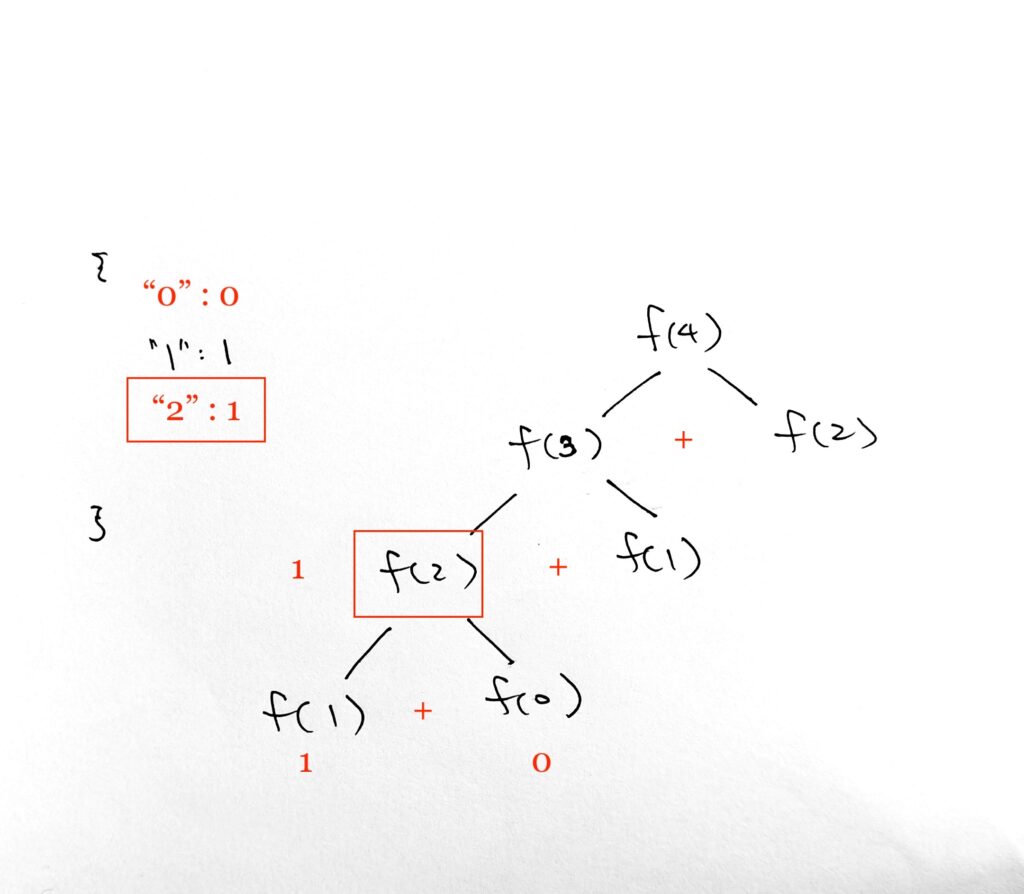

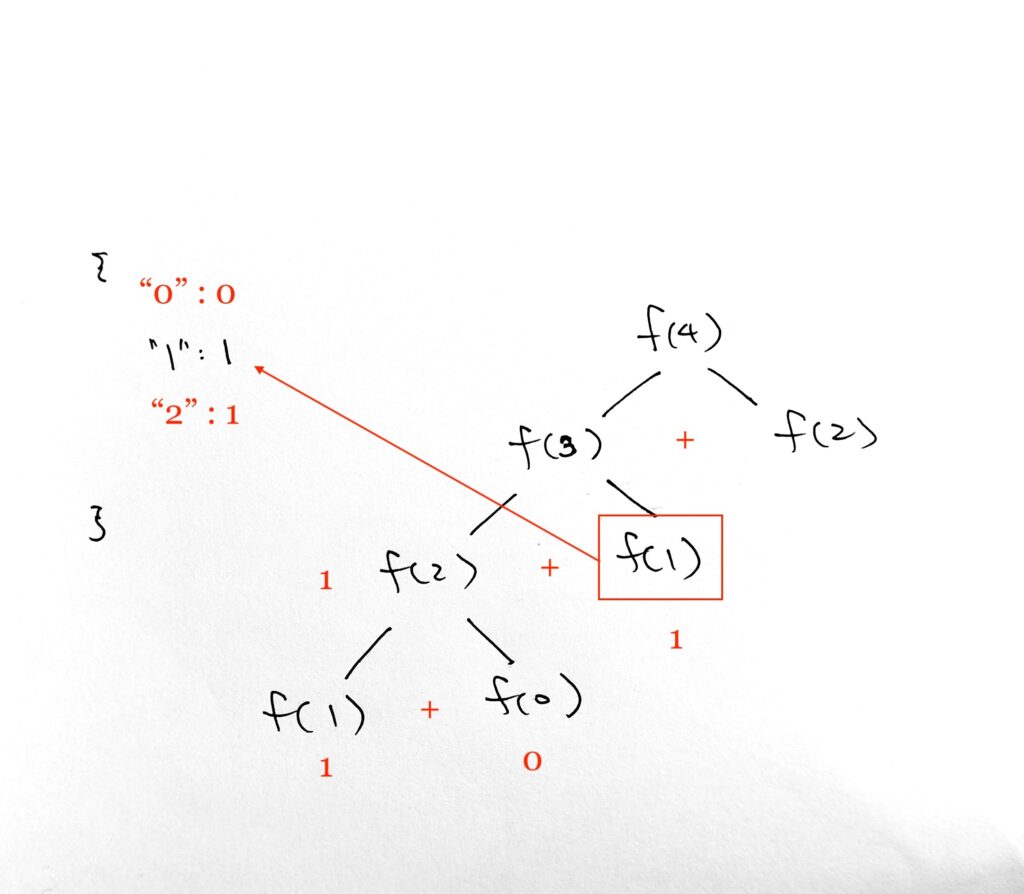

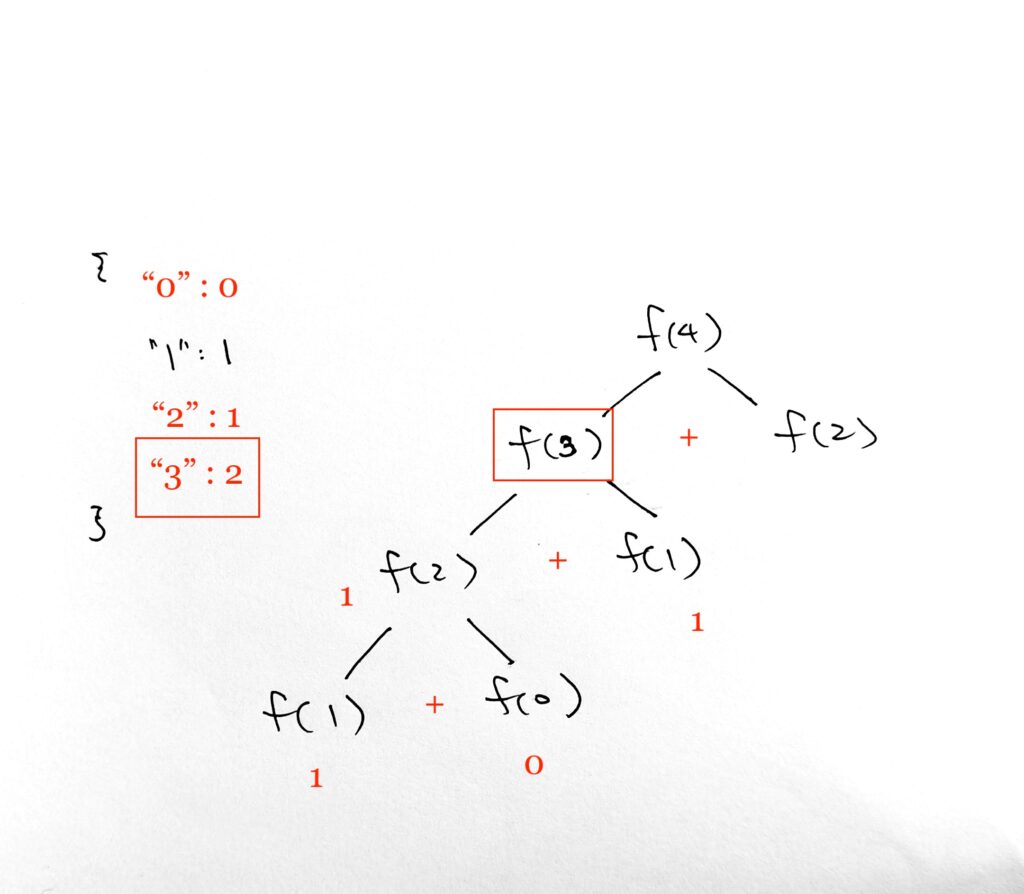

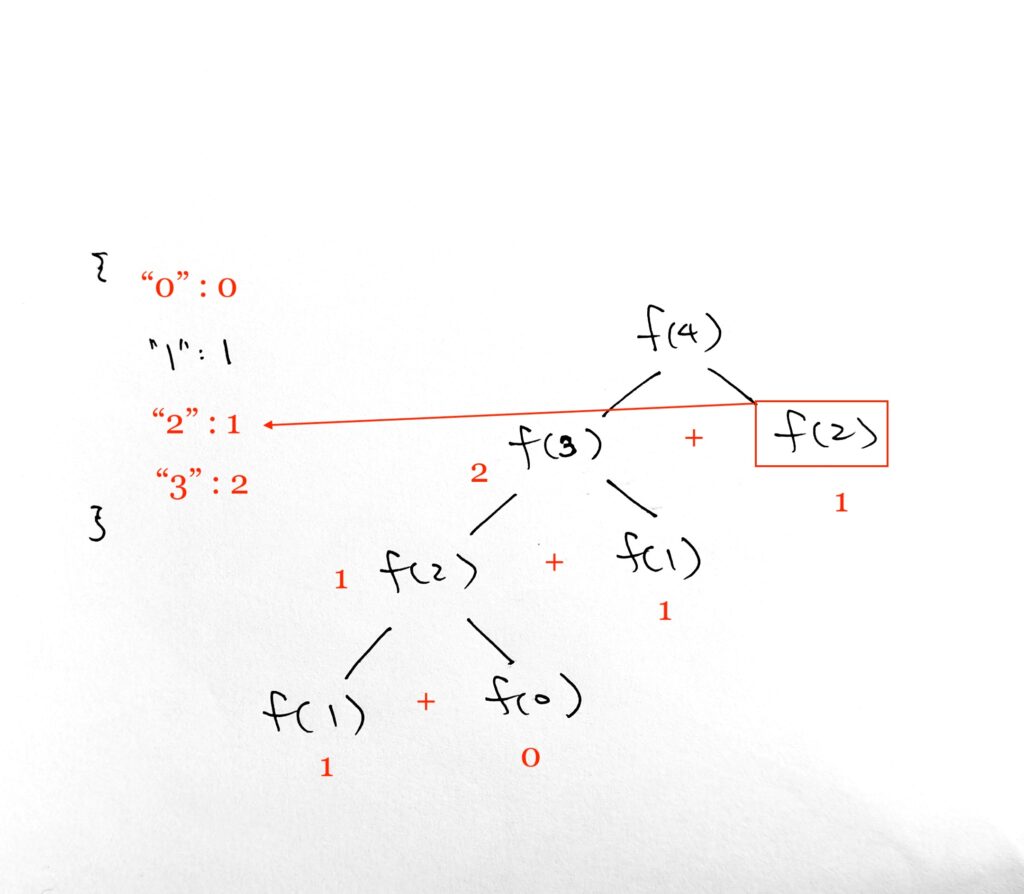

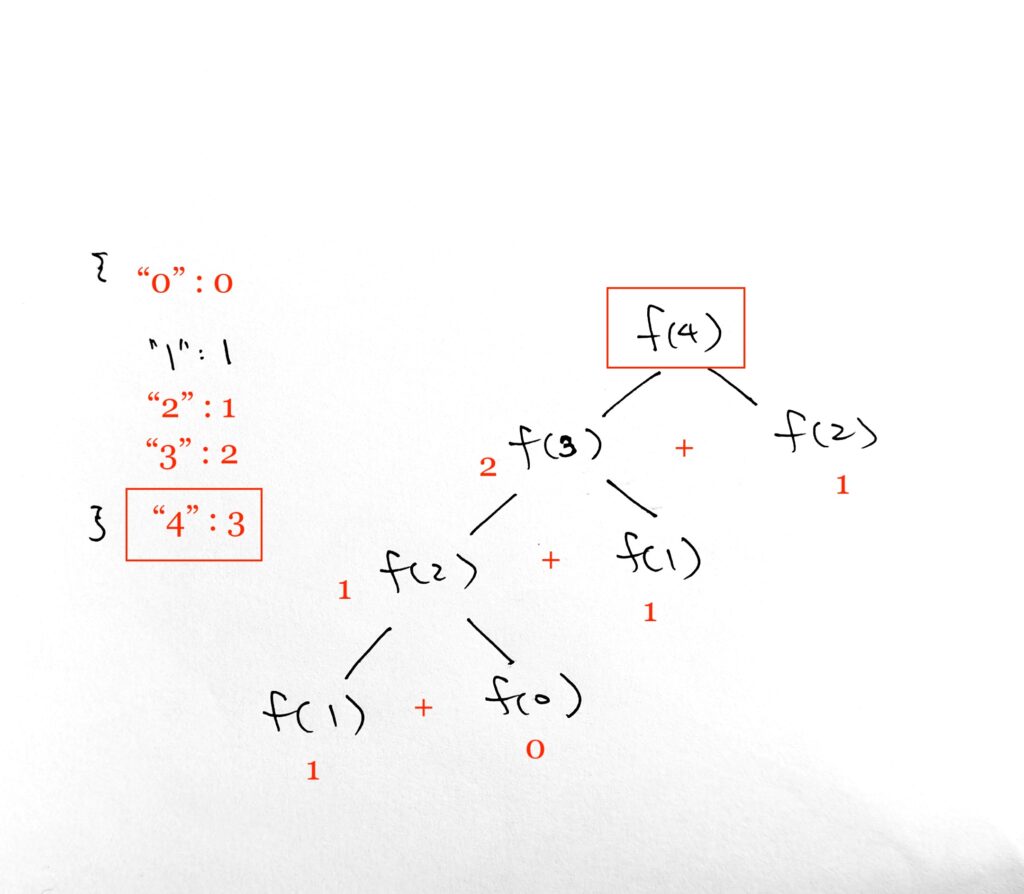

Say we put in a parameter of 5. We’d draw out a three of how our recursive calls would go. Where as we drill down to where parameter n is 0 or 1. That is the base case

where we return their respective numbers

recursiveFib(5)

recursiveFib(4) + recursiveFib(3)

recursiveFib(3) + recursiveFib(2) recursiveFib(2) + recursiveFib(1)

recursiveFib(2) + recursiveFib(1) recursiveFib(1) + recursiveFib(0) recursiveFib(1) + recursive(0) recursiveFib(1) + recursiveFib(0)

As you can see, we make calls to recursiveFib(2) three times. recursiveFib(1) five times. And recursiveFib(3) two times.

This is a lot of recalculations. The concept of memoization is to store them in a cache so that we only calculate each parameter once. Any future calls would simply take O(1) time and we can access the results immediately.

Here, we create a function that contains a key/value cache with a simple JS literal object called memo. Then we return our fib function from above. We put it just below memo. Since we return this function to elsewhere, our fib function can access memo via closure.

Before ANY kind of recursive calculation is done, we first comb through our memo to see if the n exists. If it exists, it means we have already processed it. We just access. If it’s not found, we move on to calculate the fib number for n. The recursion is exactly the same. Except that we make sure to put the result into our memo cache when done.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 |

const memoFib = function() { console.log('returning to you a fib function that memoized') let memo = { } // access by closure // return the fib function // access our key/value table via closure return function fib(n) { if (n in memo) { console.log(`access cache of ${memo[n]} from ${n.toString(10)}`) return memo[n.toString(10)] } else { if (n <= 1) { // assign 0 to 0, 1 to 1 memo[n.toString(10)] = n console.log(`stored ${n} to ` + memo[n.toString(10)]); } else { let result = fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2) ; memo[n.toString(10)] = result; console.log(`stored ${result} at ${n.toString(10)}`) } return memo[n.toString(10)] } } } |

Going through the details

We start off by processing fib(5), which is fib(4) + fib(3)

By order, we then recurse fib(4), which is fib(3) + fib(2)

By order, we then recurse fib(3), which is fib(2) + fib(1)

By order, we then recurse fib(2), which is fib(1) + fib(0)

By order, we then recurse fib(1), which is the end case.

log “stored 1 to 1”

So we create new cache value 1 for key 1

Moving on to fib(0), its an end case. So we create new cache value 0 for key 0

log “stored 0 to 0”

The addition of both gives fib(2) = 1 + 0.

We create new cache value 1 for key 2.

On fib(3) = fib(2) + fib(1), we move on to fib(1)

Notice that we have a key/value in our cache for key 1. Hence we simply access it. This saves us calculation and processing time.

We then have fib(3) = 1 + 1 = 2.

We create cache value 2 for key 3.

On fib(4) = fib(3) + fib(2), we move on to fib(2). Notice again that key 2 already exists. We can save time again and just get the cache.

Finally, fib(4) = 2 + 1 = 3. We insert cache value 3 for key 4.

– Fibonacci recursive functions are a “pure” functions — that is, the same input value will always return the same output. This is a necessary condition for using memoization, as our cache needs to remember ONE SINGLE return values for the inputs.

– Memoization trades time for space — we must create a space in our cache for every input needed to calculate our result.

Memoization Components

We first create a state with input 0.

We then create a button that handles an input.

In the input, we put the # of times we want to repeat the input being changed to 8.

you’ll notice as we use setTimeout to change it the state 3 times to the value 8. The render function gets called 3 times, even though the state.input is always 8.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 |

class App extends React.Component { constructor() { super(); this.state = { input: 0 } this.recursiveFib = n => { if (n <= 1) { return n } let result = this.recursiveFib(n-1) + this.recursiveFib(n-2); return result; } this.handleInput = this.handleInput.bind(this); } // prototype functions handleInput = evt => { console.log('changed input to', evt.target.value) for (let i =0 ; i < evt.target.value; i++) { // we loop n times and set the state to 8 setTimeout( () => { console.log('called setState'); this.setState({ input: 8 }) }, 1000*i ); } } render() { console.log('-- render --'); const { input } = this.state; console.log('input', input); return ( <div className="App"> <header className="App-header"> <input onChange = {this.handleInput} /> <h2> {this.recursiveFib(8) } </h2> </header> </div> ); } } |

output:

input to 3

called setState

— render —

input 8

called setState

— render —

input 8

called setState

— render —

input 8

Improve with PureComponent

If we were to extend PureComponent, it actually shallow checks to see if the previous prop/state is the same as the current prop/state.

If its the same, we won’t re-render.

Simply change this line of code:

|

1 |

class App extends React.Component { |

to

|

1 |

class App extends React.PureComponent { |

result:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

changed input to 5 called setState -- render -- input 8 (4) called setState |

Therefore PureComponent improves your performance.

Improving Performance with Memoization

Let’s write a simple function where we wait for some seconds.

In your fib function, right before you return a value, let’s simulate that the calculation takes 1 second.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

function wait(milliseconds=0) { console.log('waiting ' + milliseconds/1000 + ' seconds'); var now = Date.now() var end = now + milliseconds while (now < end) { now = Date.now() } } |

So we put wait(1000) in front of all returns in our recursiveFib.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

this.recursiveFib = n => { if (n <= 1) { wait(1000); return n } let result = this.recursiveFib(n-1) + this.recursiveFib(n-2); wait(1000); return result; } |

Let’s put recursiveFib in our render. Whenever we input a number, it calls setState in the input, and thus will call our render.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 |

render() { console.log('-- render --'); const { input } = this.state; console.log('rendering fibonacii input of ', input); return ( <div className="App"> <header className="App-header"> <input onChange = {this.handleInput} /> <h2> {this.recursiveFib(input) } </h2> </header> </div> ); } |

When we run all the code together, you’ll notice that it it gets stuck processing all the simulated processing time (of 1 sec) before the render.

So this is to simply show that if we have some calculations that take up a lot of time, and its hurting our render time, how do we further improve performance with memoization?

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 |

class App extends React.PureComponent { constructor() { super(); this.state = { input: 0 } this.recursiveFib = n => { if (n <= 1) { wait(1000); return n } let result = this.recursiveFib(n-1) + this.recursiveFib(n-2); wait(1000); return result; } this.handleInput = this.handleInput.bind(this); } // prototype functions handleInput = evt => { console.log('changed input to: ', evt.target.value); this.setState({ input: evt.target.value }) } render() { console.log('-- render --'); const { input } = this.state; console.log('rendering fibonacii input of ', input); return ( <div className="App"> <header className="App-header"> <input onChange = {this.handleInput} /> <h2> {this.recursiveFib(input) } </h2> </header> </div> ); } } |

Because every single node must be calculated from scratch, we must calculate for a total of 9 nodes. If each node takes 1 second, then it takes 9 seconds.

output:

changed input to: 4

— render —

rendering fibonacii input of 4

waiting 1 seconds

waiting 1 seconds

waiting 1 seconds

waiting 1 seconds

waiting 1 seconds

waiting 1 seconds

waiting 1 seconds

waiting 1 seconds

waiting 1 seconds

So total processing time for standard fib is 9 seconds.

Let’s change by using our memoizationFib.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 |

this.memoFib= () => { console.log('returning to you a fib function that memoized') let memo = { } // access by closure return function fib(n) { if (n in memo) { wait(1000); return memo[n.toString(10)] } else { if (n <= 1) { // assign 0 to 0, 1 to 1 memo[n.toString(10)] = n } else { let result = fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2) ; memo[n.toString(10)] = result; } wait(1000); return memo[n.toString(10)] } } } |

Now instead of 9 seconds, we simply wait 7 seconds.

output:

f(4)

App.js:106 f(3)

App.js:106 f(2)

App.js:106 f(1)

App.js:65 waiting 1 seconds

App.js:106 f(0)

App.js:65 waiting 1 seconds

App.js:65 waiting 1 seconds

App.js:106 f(1)

App.js:65 waiting 1 seconds

App.js:65 waiting 1 seconds

App.js:106 f(2)

App.js:65 waiting 1 seconds

App.js:65 waiting 1 seconds

The differences get bigger as the recursion increases.

For standard Fib(9) when you calculate everything, its 109 seconds.

Whereas if you use memoization, and save calculations, it only takes 17 seconds. This is because you avoid re-calculating subtrees.

React Decorators

|

1 2 3 4 |

@setTitle('Profile') class Profile extends React.Component { //.... } |

title is a string that will be set as a document title.

It is a parameter passed in from above (‘Profile’).

WrappedComponent is the Profile component displayed above.

Hence, @setTitle(title)(wrappedComponent) is what’s happening. We want to decorate the class Profile by returning a class

of our own with specific attributes and functionalities.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

const setTitle = (title) => (WrappedComponent) => { return class extends React.Component { componentDidMount() { document.title = title } render() { return <WrappedComponent {...this.props} /> } } } |

How do you conditionally render components?

In some cases you want to render different components depending on some state. JSX does not render false or undefined, so you can use conditional short-circuiting to render a given part of your component only if a certain condition is true.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

const MyComponent = ({ name, address }) => ( <div> <h2>{name}</h2> {address && <p>{address}</p> } </div> ) |

If you need an if-else condition then use ternary operator.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

const MyComponent = ({ name, address }) => ( <div> <h2>{name}</h2> {address ? <p>{address}</p> : <p>{'Address is not available'}</p> } </div> ) |

What will happen if you use props in initial state?

Parent component passes a prop down to the Child component. The Child component will first be constructed via the constructor method. Then we assign the prop to the state.

But what if the parent component updates its prop? Since the constructor only gets called once, the child component’s state won’t get the updated prop.

The below component won’t display the updated input value:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 |

class MyComponent extends React.Component { constructor(props) { // <-- only called once. Any prop updates after this won't get assigned. super(props) this.state = { records: [], inputValue: this.props.inputValue }; } render() { return <div>{this.state.inputValue}</div> } } |

In order to get the updated props value, we must use props inside render method.

Now, anytime the parent component updates the prop, this child component will get the update.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

class MyComponent extends React.Component { constructor(props) { super(props) this.state = { record: [] } } render() { return <div>{this.props.inputValue}</div> } } |

use setState() in componentWillMount() method?

ref – https://stackoverflow.com/questions/52168047/is-setstate-inside-componentdidmount-considered-an-anti-pattern

You may call setState() immediately in componentDidMount(). It will trigger an extra rendering, but it will happen before the browser updates the screen. This guarantees that even though the render() will be called twice in this case, the user won’t see the intermediate state. Use this pattern with caution because it often causes performance issues. In most cases, you should be able to assign the initial state in the constructor() instead. It can, however, be necessary for cases like modals and tooltips when you need to measure a DOM node before rendering something that depends on its size or position.

It is recommended to avoid async initialization in componentWillMount() lifecycle method.

componentWillMount() is invoked immediately before mounting occurs. It is called before render(), therefore setting state in this method will not trigger a re-render. Avoid introducing any side-effects or subscriptions in this method. We need to make sure async calls for component initialization happened in componentDidMount() instead of componentWillMount().

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

componentDidMount() { axios.get(`api/todos`) .then((result) => { this.setState({ messages: [...result.data] }) }) } |

How are events different in React?

Handling events in React elements has some syntactic differences:

– React event handlers are named using camelCase, rather than lowercase.

– With JSX you pass a function as the event handler, rather than a string.

How to use styles in React?

The style attribute accepts a JavaScript object with camelCased properties rather than a CSS string. This is consistent with the DOM style JavaScript property, is more efficient, and prevents XSS security holes.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

const divStyle = { color: 'blue', backgroundImage: 'url(' + imgUrl + ')' }; function HelloWorldComponent() { return <div style={divStyle}>Hello World!</div> } |

Error Boundary in React

ErrorBoundary.js

Error boundaries are components that catch JavaScript errors anywhere in their child component tree, log those errors, and display a fallback UI instead of the component tree that crashed.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 |

import React from 'react'; class ErrorBoundary extends React.Component { constructor(props) { console.log('---ErrorBoundary---'); super(props) this.state = { hasError: false } } componentDidCatch(error, info) { this.setState({ hasError: true }) } render() { if (this.state.hasError) { // You can render any custom fallback UI return <h1>{'Something went wrong.'}</h1> } return this.props.children } } export default ErrorBoundary; |

App.js

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 |

import React from 'react'; import './App.css'; import ErrorBoundary from './ErrorBoundary'; class Item extends React.Component { constructor(props) { super(props); } render() { const {name} = this.props; if (name!== '1345577') { throw new Error("ERROR"); } return ( <div className="form-group"> <label className="col-xs-4 control-label">{name}</label> <div className="col-xs-8"> <input type='text' className='form-control' /> </div> </div> ); } } class App extends React.Component { constructor() { super(); this.state = { // array of objects // each object has property name, id list: [] }; this.addItem = this.addItem.bind(this); } //prototype methods run in strict mode. addItem() { const id = new Date().getTime().toString(); this.setState({ list: [ {name: id, id} , ...this.state.list] //list: [...this.state.list, {name: id, id} ] }); } render() { const { list } = this.state; return ( <div className="App"> <ErrorBoundary> <button className='btn btn-primary' onClick={this.addItem}> <b>Add item</b> to the beginning of the list </button> <h3>Better <code>key=id</code></h3> <form className="form-horizontal"> {this.state.list.map((todo) => <Item {...todo} key={todo.id} /> )} </form> </ErrorBoundary> </div> ); } } export default App; |