http://javascript.info/function-prototype

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 |

function Rabbit() { console.log("Rabbit Constructor"); } console.log(Rabbit.prototype); console.log(Rabbit.prototype.constructor); Rabbit.prototype = { name: "not entered" } console.log(Rabbit.prototype); console.log(Rabbit.prototype.constructor); Rabbit.prototype.copy = function() { // return new Person(this.name); // just as bad return new Rabbit(); }; console.log(Rabbit.prototype); console.log(Rabbit.prototype.constructor); var a = new Rabbit(); console.log(a.__proto__); console.log(a.__proto__.constructor); |

[DRAWING HERE]

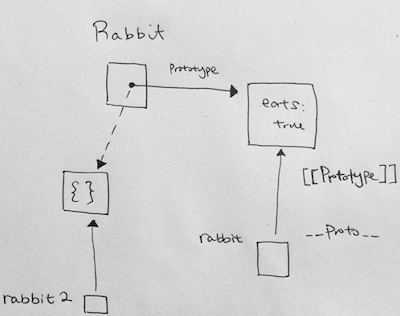

In modern JavaScript we can set a prototype using __proto__.

But in the old times, there was another (and the only) way to set it: to use a “prototype” property of the constructor function.

It is known that, when “new F()” creates a new object…

the new object’s [[Prototype]] is set to F.prototype

In other words, if function F has a prototype property with a value of the object type, then the “new” operator uses it to set [[Prototype]] for the new object.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 |

"use strict" function ParentRabbit() { this.eats = true; this.parentDisplay = function() { console.log("-- ParentRabbit parentDisplay --"); console.log("Does it eat? " + this.eats); } } // function object function Rabbit(newName) { this.rabbitName = newName || "Not Given"; this.display = function() { console.log("-- Rabbit display --"); console.log("name: "+this.rabbitName); } } // F has prototype property with a value to object var animal = new ParentRabbit("White Rabbit"); Rabbit.prototype = animal; // rabbit.__proto__ == animal // the "new" operator uses it to // set [[Prototype]] for the new object let rabbit = new Rabbit(); rabbit.display(); rabbit.parentDisplay(); console.log("accessing parent's property"); console.log(rabbit.eats); |

Setting Rabbit.prototype = animal literally states the following: “When a new Rabbit is created, assign its [[Prototype]] to animal”.

Constructor Property

As stated previous, we have the “prototype” property point to whatever object we want as the parent class to be inherited from future “new”-ed functions.

However, what is this “prototype” property before our assignment?

Every function has the “prototype” property even if we don’t supply it.

The default “prototype” property points to an object with the only property constructor that points back to the function itself.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 |

"use strict" function Rabbit() { this.rabbitName = "not entered"; this.display = function() { console.log(this.rabbitName); } } // default prototype property console.log(Rabbit.prototype); // Rabbit {} //constructor points back to Function type Rabbit console.log(Rabbit.prototype.constructor); // [Function: Rabbit] function ParentRabbit() { this.rabbitType = "Rare Breed"; this.displayBreed = function() { console.log(this.rabbitType); } } console.log(ParentRabbit.prototype); // Rabbit {} // constructor points to Function type ParentRabbit console.log(ParentRabbit.prototype.constructor); // [Function: ParentRabbit] console.log("sets it to instance of ParentRabbit"); var animal = new ParentRabbit(); Rabbit.prototype = animal; |

You can check it like this:

|

1 |

console.log( Rabbit.prototype.constructor == ParentRabbit ); // true |

Rabbit prototype by default

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

function Rabbit() { this.rabbitName = "not entered"; this.display = function() { console.log(this.rabbitName); } } // default prototype property console.log(Rabbit.prototype); // Rabbit {} console.log(Rabbit.prototype.constructor); // constructor points back to Function type Rabbit |

By default whatever objects created from “new Rabbit()” will inherit from Rabbit.

The instance ‘rabbit’ has constructor property which points to Rabbit.

We can use constructor property to create a new object using the same constructor as the existing one.

Like here:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

function Rabbit(name) { this.name = name; alert(name); } let rabbit = new Rabbit("White Rabbit"); let rabbit2 = new rabbit.constructor("Black Rabbit"); |

Future manipulations of the prototype property

JavaScript itself does not ensure the right “constructor” value.

Yes, it exists in the default object that property prototype references, but that’s all. What happens with it later – is totally on us.

In this example, we see that we repointed the prototype to a totally different object. Thus, other instances of Rabbit, will be deriving from the object with property jumps: true.

The assumption that instances of Rabbit will have a ‘Rabbit’ constructor will then be false.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

function Rabbit() {} Rabbit.prototype = { jumps: true }; let rabbit = new Rabbit(); alert(rabbit.constructor === Rabbit); // false |

So, to keep the right “constructor” we can choose to add/remove properties to the default “prototype” instead of overwriting it as a whole:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

function Rabbit() {} // Not overwrite Rabbit.prototype totally // just add to it Rabbit.prototype.jumps = true // the default Rabbit.prototype.constructor is preserved |

Or you can reconstruct it yourself. Just make sure to include the constructor property and set it to your this object:

|

1 2 3 4 |

Rabbit.prototype = { jumps: true, constructor: Rabbit }; |

The only thing F.prototype does: it sets [[Prototype]] of new objects when “new F()” is called.

The value of F.prototype should be either an object or null: other values won’t work.

The “prototype” property only has such a special effect when is set to a constructor function, and invoked with new.

|

1 2 3 4 |

let user = { name: "John", prototype: "Bla-bla" // no magic at all }; |

By default all functions have F.prototype = { constructor: F }, so we can get the constructor of an object by accessing its “constructor” property.

Gotchas

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

function Rabbit() {} Rabbit.prototype = { eats: true }; let rabbit = new Rabbit(); // rabbit's __proto__ is now set to Rabbit Rabbit.prototype = {}; console.log( rabbit.eats ); // true |

The assignment to Rabbit.prototype sets up [[Prototype]] for new objects. The new object ‘rabbit’ then points to Rabbit. The instance rabbit’s [[Prototype]] then is pointing to Rabbit’s default prototype object with its constructor property.

Then Rabbit’s prototype points to an empty object. However, rabbit’s [[Prototype]] already is referencing Rabbit’s default prototype object with its constructor property. Hence that’s why rabbit.eats is true.

Problem 1

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

function Rabbit() {} Rabbit.prototype = { eats: true }; let rabbit = new Rabbit(); Rabbit.prototype = {}; alert( rabbit.eats ); // ? |

solution: true

Problem 2

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

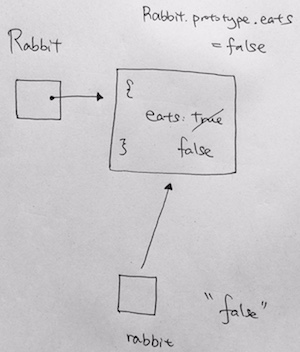

function Rabbit() {} Rabbit.prototype = { eats: true }; let rabbit = new Rabbit(); Rabbit.prototype.eats = false; alert( rabbit.eats ); // ? |

Solution: false

Problem 3

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

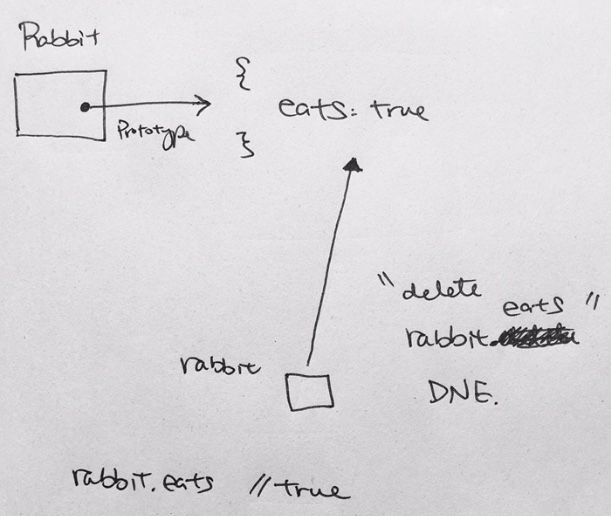

function Rabbit() {} Rabbit.prototype = { eats: true }; let rabbit = new Rabbit(); delete rabbit.eats; alert( rabbit.eats ); // ? |

Solution:

All delete operations are applied directly to the object. Here delete rabbit.eats tries to remove eats property from rabbit, but it doesn’t have it. So the operation won’t have any effect.

Problem 4

|

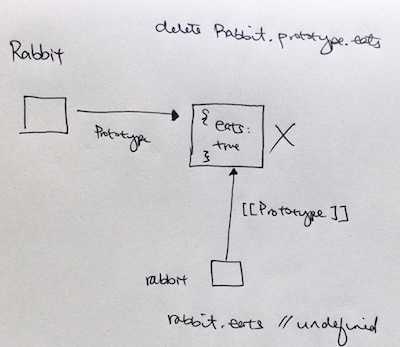

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

function Rabbit() {} Rabbit.prototype = { eats: true }; let rabbit = new Rabbit(); delete Rabbit.prototype.eats; alert( rabbit.eats ); // ? |