Look at the problems right away. They are multiple choice problems where it tells you which paragraph to read.

This is by far the hardest as you’re not sure which paragraph is which and this section should be left for last.

The first one to read is for first paragraph.

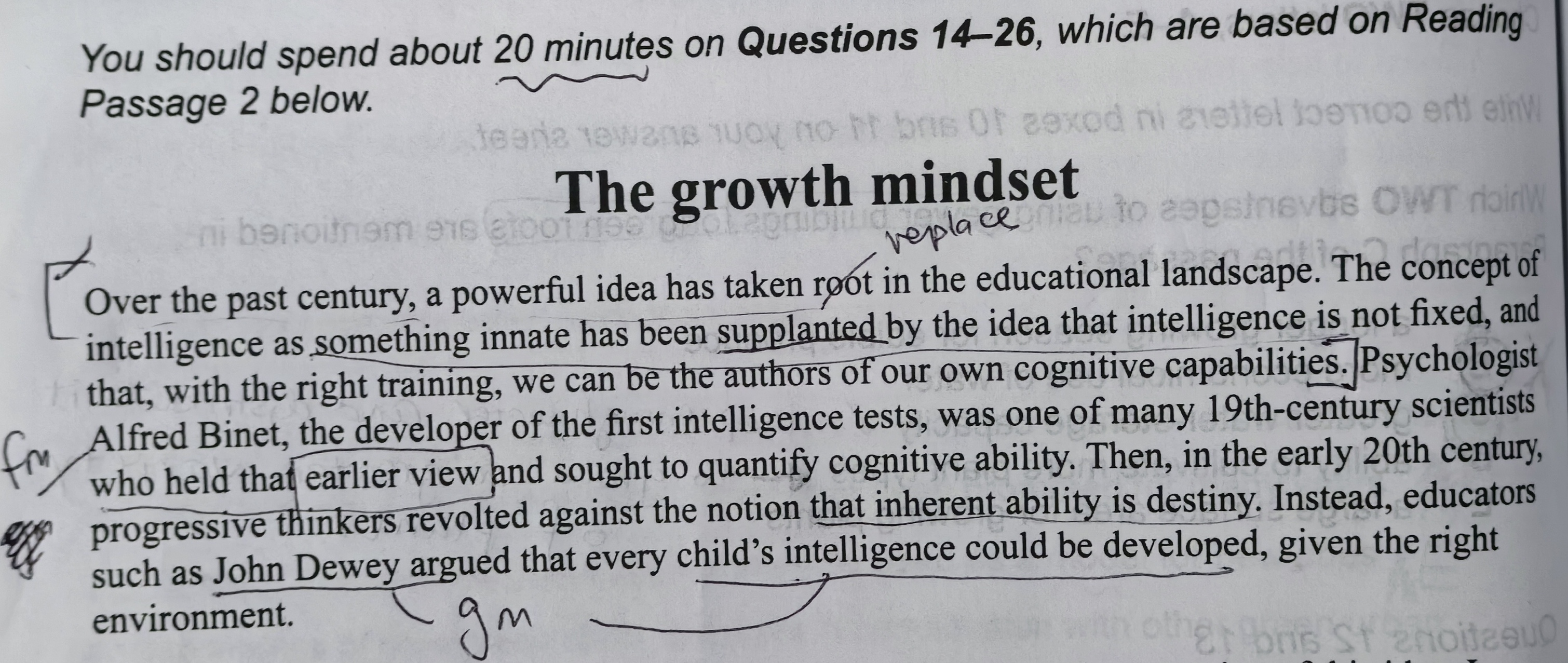

The answer is B when ideas about the nature of intelligence began to shift

This is the exact paraphrase of the first sentence (hook):

“Over the past century, a powerful idea has taken root in the educational landscape”.

When you do process of elimination, we know that A and D cannot be it. B and C seems OK. B is closer to the paraphrase of the hook, but what about C?

Now, the other potential answer is the main-thesis, which is “Instead, educators …. argued that every child’s intelligence could be developed…”

Notice that answer C uses “scientists” and the thesis uses “educators”, and there was a use of “psychologist” in the paragraph. So it doesn’t match. Thus, B is the best answer. However, for context, always read the whole paragraph. Its just that when you’re down to selecting the answer, analyze the first and last sentence.

For 15, it tells you right away read the second paragraph to see “how schools encourage students to”.

Paragraph 2

Again, you must read the whole paragraph for context. There is a word that italicized: “believed”.

It says that athletes believed their way to the top. This is a synonym for confidence. And that schools is coaxing students students to see failures as a chance to improve themselves. “smart is something you can get”

So, process of elimination:

A obvious not

B not really – this paragraph is about improving, and believing. Not realize goals.

C Best choice. confidence is synonymous with believing.

D obvious not

For 16 It tells you right away to look in the third paragraph

Paragraph 3

it asks “the writer suggests that students with a fixed mindset” something.

As a habit, read the whole paragraph. The paragraph says that one group is pushed for their innate ability, and the other group is pushed for their efforts. The second group (effort, growth mindset) were more likely to put effort into future tasks.

fixed mindset –> fear of failure

This is just paraphrase for “are afraid to push themselves beyond what they see as their limitations”. So the answer is D

Questions 17-22 are matching List of People

This is medium hard and should be left for the middle. Let’s see if there’s anything easier.

Now we move on to paragraph 4, but we don’t see any authors in paragraph 4 so we skip.

We move on to paragraph 5, and then see Andrew Gelman. At this point, it’s about paraphrasing.

In the article, the passage is:

‘their research designs have enough degrees of freedom that they couldn’t take their data to support just about any theory at all.”

If you look at 17- 22, it’s kind of confusing because the answers all seem like they can go either way.

So my logic is that just keep reading the passage for an author until you get a more obviousi answer.

This came with the author Carl Dweck (B) “she argues that her work has been misunderstood and misapplied in a range of ways…..her theories are being misappropriated by being conflated with the self-esteem movement”.

18’s sentence mostly matches this so 18 should be B

17

18 B

19

20

21

22

If you keep reading into the next paragraph, you’ll see that “David yeager and Gregoy Walton” claim that interventions should be delivered ina. subtle way Go back to your questions and if you read it, 20 pops up to match E, because 20 says:

“the growth mindset should be promoted without students being aware of it” which is a great paraphrase for E.

17

18 B

19

20 E

21

22

Alfred Binet (A) was mentioned in paragraph 1 (intro) so when it comes to a list of people, you’ll have to scan the entire story to find them. Alfred Binet mentions intelligence being innate, so this matches up with 19 the best.

17

18 B

19 A

20 E

21

22

You keep going in this pattern

Yes Not Not Given questions

These questions are the easiest because it tells you which paragraph to look at. You should try to do this first.

23 – Dweck has handled criticisms of her work in an admirable way.

The answer is Yes because in Paragraph 7, it says:

“she deserves great credit for responding to it and adapting her work accordingly.”

This is just paraphrase for Dweck handling criticism.

24 – Students’ self-perception is a more effective driver of self-confidence than actual achievement is.

Self-Perception on self confidence > Achievement on self confidence?

This has been disapproved in paragraph 9:

The min-thesis statement matches we’re saying here: “There is a strong correlation between self-perception and achievement”.

self-perception –> achievement.

However!

“but there is evidence to suggest that actual effect of achievement on self-perception is STRONGER”

Achievement –> self-perception √

So the answer is NO. Student’s actual achievement has more effect on self-perception.

25. Recent evidence about growth mindset interventions has attracted unfair coverage in the media

In the next paragraph, we read that

“Recent evidence would suggest that growth mindset interventions are not the elixir of student learning.”

Nothing was mentioned about the media, so it would be “not given”.

Not Given.

26 – Deliberate attempts to encourage students to strive for high achievement may have a negative effect.

The last paragraph depicts clearer the message that “Teaching concrete skills such as how to write an effective introduction to an essay then praising students’ effort in getting there is probably a far better way of improving confidence than telling them how unique they are.”

Hence, “Deliberate attempts to encourage students to strive for high achievement” = praising their effort

may have a negative effect is True